I ONCE KNEW A WOMAN WHO, without warning after eighteen years of what had appeared to be a highly successful marriage, served her ambitious and renowned husband with divorce papers.

I ONCE KNEW A WOMAN WHO, without warning after eighteen years of what had appeared to be a highly successful marriage, served her ambitious and renowned husband with divorce papers.

In shock, the debonair New York businessman, who had given his wife everything that cosmopolitan life could offer, asked her: “Why?”

“Why?” she responded, partly amused. “Because, my darling . . . I would rather be alone, and live my life, than be with you and live only yours.”

She moved to Santa Fe, he died of Leukemia, and the rest is a mystery that has preoccupied me on more than one evening lately when, pondering my daughter’s struggle to find Mr. Right, I have asked myself: Why? Why is it so difficult to find someone to share a life with? And why is it that, in this, the twenty-first century, it is still the woman who is expected to conform to the needs of the man?

Over the years, I have heard every form of excuse: it’s important for a man to be “authentic;” he must be “true to himself.” And what woman would ever expect her man to be anything other than authentic or true to himself?

So, why is it that these men are so often attracted to their extreme opposites? Like that cowboy, Beauregard Decker, in Bus Stop, who falls for the beautiful Cherie, and expects her to abandon her dreams of Hollywood for the flats of Montana, for no better reason than he loves her. It strikes me as wanting the cheetah for a pet, but then insisting on feeding it hay.

So, why is it that these men are so often attracted to their extreme opposites? Like that cowboy, Beauregard Decker, in Bus Stop, who falls for the beautiful Cherie, and expects her to abandon her dreams of Hollywood for the flats of Montana, for no better reason than he loves her. It strikes me as wanting the cheetah for a pet, but then insisting on feeding it hay.

Marriage is a daunting step—the most important one you will take in your life. And, I think it is for this reason that when Pitou asked me If I would marry him, I responded with a question of my own:

“Because I love you,” he answered.

“And, not getting it on paper will change that?”

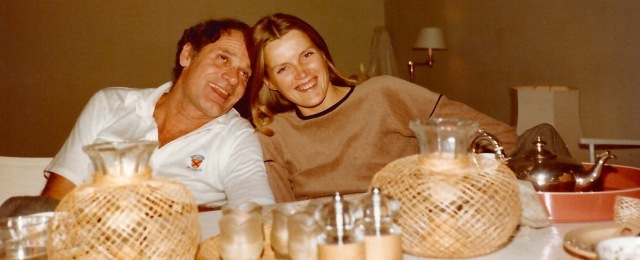

I was barely twenty, and had only loved one other man in my life—Bruce. I admit, as crazy as I was about Pitou, the idea of tying myself to one man forever scared me to death. He, however, was forty-six. He’d been divorced from Suzy for a decade. Tired of bachelor life, he wanted nothing more than to settle down and start a family.

“Look,” I said, “I could understand getting married if a kid were involved. The family unit, that sense of belonging, it’s important to a child. So, here is what I propose. If I get pregnant, we’ll get married. But, before that . . . what’s the point?”

He never brought the subject up again. But, on a morning in April of 1976 when, suddenly, I found myself running to the toilet to throw up, he was all-smiles.

The second I became pregnant, I knew it; a sensation that, in the four and a half years we had been together, I had never felt. And yet, on the morning when I conceived, inexplicably, I was sure of it.

“I’m pregnant,” I whispered to myself, as I lay wrapped in pure linen sheets.

The prospect of marriage, finally, was upon me.

In the weeks that followed, my colleagues at Merrill kept asking the same question.

“Are you okay? You seem different.”

More than anything, I was tired. All I wanted to do was stay in bed.

Sitting at my desk, trying to keep my eyes open, the click of Ramiro’s Zippo lighter snapped me out of a daze.

“You look green, Berenice. Get the hell out of here and get some sleep.”

I did, and conked out for the next 24 hours.

The apartment was quiet. Living on the park, all I could hear were the sounds of birds chirping and children playing on the carousel and swings, and laughing to the outdoor performance of Punch and Judy. At times, in only a half sleep, I could hear the bedroom door open, as Pitou peeked in to see how I was doing.

“Est-elle vraiment enceinte?” [1] he wondered.

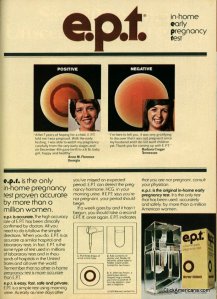

Back then, you couldn’t just piss on a stick and get an instant response. You, either, went to a clinic, and had a physician examine you, or, after a sufficient amount of time had elapsed, you bought a test tube at the local pharmacy containing magic chemicals that interacted with your urine over a period of eighteen hours, after which –voila—you got the response. If nothing formed at the bottom of the tube, you weren’t pregnant. But, if a little red circle appeared, then, your entire life was about to change.

Back then, you couldn’t just piss on a stick and get an instant response. You, either, went to a clinic, and had a physician examine you, or, after a sufficient amount of time had elapsed, you bought a test tube at the local pharmacy containing magic chemicals that interacted with your urine over a period of eighteen hours, after which –voila—you got the response. If nothing formed at the bottom of the tube, you weren’t pregnant. But, if a little red circle appeared, then, your entire life was about to change.

Pitou bought the test tube. I placed it on a plastic rack that had come with the box. It stood for an entire day on the marble counter of our bathroom sink, and he checked for the appearance of that all mighty circle—every hour on the hour. When it finally emerged, he picked up the tube and hid it from me, afraid I might throw it away.

I don’t know where he put it, or how long he kept it. All I remember is that he couldn’t stop smiling. I had never seen him so happy.

Bill

The prior summer, we had rented a finca in the hills of Ibiza, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. It had belonged to friends of ours, Bill and Huguette McLaughlin. Bill was a Peabody award-winning diplomatic and foreign correspondent who had headed bureaus in Germany and Lebanon for CBS News. He was living in Paris when I met him, and had already covered the murder of the eleven Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics and the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, as well as having interviewed everyone in the Middle East from Yasser Arafat to Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal.

When I mentioned, one night over dinner, that Pitou and I needed to get away but weren’t sure where to go, Huguette presented us with the keys to the white-washed plaster walls of their quaint little farm-house off the coast of Spain. Pitou was agitated that August, disturbed against a backdrop of crystal blue water and serenity. He spent the entire time we were there reading, reflecting, as if to take stock of his life up until that point.

When I mentioned, one night over dinner, that Pitou and I needed to get away but weren’t sure where to go, Huguette presented us with the keys to the white-washed plaster walls of their quaint little farm-house off the coast of Spain. Pitou was agitated that August, disturbed against a backdrop of crystal blue water and serenity. He spent the entire time we were there reading, reflecting, as if to take stock of his life up until that point.

He had led such an extraordinary life—of glamour and excitement, with iconic people of exceptional intelligence, grace and wit. He had lived among the beautiful people. Indeed, he was considered as one of them. A girlfriend of mine, some fifteen years older than me, who had known Pitou in the late fifties, tried one day to give me a glimpse of him back then.

“I was standing one night,” she said, “in front of New Jimmy’s.”

It was Regine’s swank nightclub on the Boulevard Montparnasse, Whose doors ouvert only to all Paris.

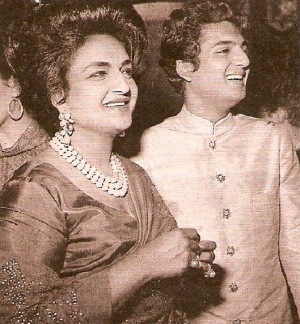

Suzy, shot by Avedon

“There were a slew of reporters,” she continued, “hanging out in the street, waiting, I didn’t know for what. Suddenly, a taxi appeared and they went absolutely wild. Pitou emerged, dressed in a Saville Row suit, with Suzy on his arm. He couldn’t get to the door of the club—the photographers were all over them, and all I could see were flash bulbs, popping, before being thrown into the gutter as the paparazzi reloaded for their next shot.”

Pitou never spoke to me of those days. For years, the only thing he ever said about them was that he “got tired of being Mr. Parker.” And yet, that summer in Ibiza, I knew he was thinking about them—thinking of the years when another woman had been by his side, had loved him, and had hoped that, together, they could forge the lifetime I was given with him.

But while his divorce from Suzy had been final, the revenge had not. Suzy’s punishment for Pitou’s dalliance with Sandra Howard was relentless, and their daughter, Georgia, had served as the perfect pawn. With Suzy’s dreams shattered, her hatred for Pitou grew exponentially, and she made sure that he felt it for years to come. Pitou’s honesty with Suzy’s attorneys, about his affair with Sandra, backfired and was used in court proceedings to portray him as the worst of Lotharios, a seducer of women of questionable integrity who could not be trusted with the safety of their daughter. With full custody of Georgia granted to the mother as a result of the father’s infidelity, Suzy decided that Pitou should only be allowed in the company of their child for short weekend intervals—while Georgia’s nurse was present. Her letters from New York, informing Pitou of the baby’s well being, were cold and sterile. They did not even begin with his name. Suzy was not writing to her former husband; she was writing to a ghost.

But while his divorce from Suzy had been final, the revenge had not. Suzy’s punishment for Pitou’s dalliance with Sandra Howard was relentless, and their daughter, Georgia, had served as the perfect pawn. With Suzy’s dreams shattered, her hatred for Pitou grew exponentially, and she made sure that he felt it for years to come. Pitou’s honesty with Suzy’s attorneys, about his affair with Sandra, backfired and was used in court proceedings to portray him as the worst of Lotharios, a seducer of women of questionable integrity who could not be trusted with the safety of their daughter. With full custody of Georgia granted to the mother as a result of the father’s infidelity, Suzy decided that Pitou should only be allowed in the company of their child for short weekend intervals—while Georgia’s nurse was present. Her letters from New York, informing Pitou of the baby’s well being, were cold and sterile. They did not even begin with his name. Suzy was not writing to her former husband; she was writing to a ghost.

In 1963, she moved to Montecito and married Bradford Dillman, the film and television actor once described as a dark-haired Ivy League character “who’s charm and confident good looks are slightly tainted by a bent smile and a darting glance that often provokes suspicion.” I would think about that description a lot over the upcoming years, as Dillman’s double nature revealed itself.

In 1963, she moved to Montecito and married Bradford Dillman, the film and television actor once described as a dark-haired Ivy League character “who’s charm and confident good looks are slightly tainted by a bent smile and a darting glance that often provokes suspicion.” I would think about that description a lot over the upcoming years, as Dillman’s double nature revealed itself.

Working in Paris as a correspondent for Match, Pitou was unable to maintain any contact with Georgia, other than through letters and his birthday and Christmas presents to the little girl. But, when the responses started arriving from a daughter who referred to Bradford as “Daddy” and her real father as “Pitou,” he gave up.

By the time we spent that summer in Ibiza, Georgia, was fifteen. Pitou hadn’t seen her in 12 years. And I knew that, more than anything, he wanted another chance to be the father to a child that had, until then, eluded him.

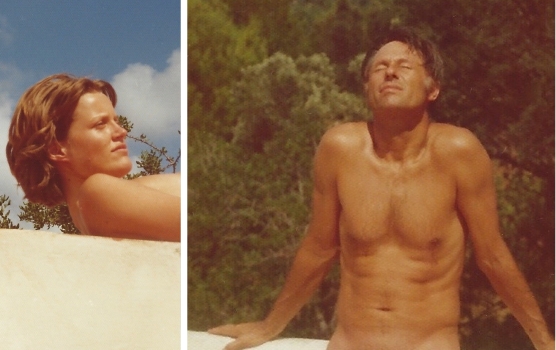

When he wasn’t reading, we spent time lounging naked in the sun while drinking good wine. The finca was gated; there wasn’t a neighbor within miles, and in the heat of the Catalan day, clothing seemed a bothersome impediment—a barrier to spontaneous sensation that we readily dispensed of. Pitou loved to sweat, and I would tease him about the odor.

When he wasn’t reading, we spent time lounging naked in the sun while drinking good wine. The finca was gated; there wasn’t a neighbor within miles, and in the heat of the Catalan day, clothing seemed a bothersome impediment—a barrier to spontaneous sensation that we readily dispensed of. Pitou loved to sweat, and I would tease him about the odor.

“I swear,” I said to him, “ if you blindfolded me in a room with one thousand men, I could pick you out in an instant . . .just by your smell.”

“Oh Bérénice,” he laughed, “Ça vas pas?”

But I could.

I was a very ordinary child and, as an adolescent, I don’t believe that I stood out in any way. I was not exceptionally popular; I didn’t belong to the “in crowd”; and I wasn’t among the brightest of my class. But, as a young woman, I fell into the hands of a man who saw my qualities and encouraged me to develop them. And that has made all the difference. For, if I have evolved into the fragment of the woman whom I came into this world wishing to become, it has been because of one man’s readiness to take me into his hands and encourage the best from me while bestowing the wisdom he had gleaned from his many years lived before. There isn’t a day that I spend where I do not think of him, do not thank him, for having made me the center of his world. I think that it was in Ibiza that I began to realize how much Pitou meant to me.

Late at night, we’d drive to the old village and walk through the cobble-stoned streets while holding hands. Back then, everyone on the island was perpetually stoned. You couldn’t walk into a café without being offered a joint from a friendly stranger. Spiritually speaking, it was still the Sixties, a time when flea markets offered the possibility of, not only a new wardrobe, but a new social circle as well.

Late at night, we’d drive to the old village and walk through the cobble-stoned streets while holding hands. Back then, everyone on the island was perpetually stoned. You couldn’t walk into a café without being offered a joint from a friendly stranger. Spiritually speaking, it was still the Sixties, a time when flea markets offered the possibility of, not only a new wardrobe, but a new social circle as well.

One Sunday morning, as I perused the make shift tables of pottery, tie-dyed T-shirts and stoner’s paraphernalia, I found myself staring at an oddly familiar face. In her late twenties, with a beautiful, blond, seven-year-old girl nipping at her waist, the woman whose gaze had caught my attention was clearly American. Suddenly, I felt myself falling into a tunnel of childhood memories.

“Wally?” I asked the woman. “Is that you?”

Startled, she stared at me questioningly.

“Do I know you?” she asked.

“It’s Bernie,” I answered, giving her my childhood nickname—the only name by which she would have recognized me.

She and her younger sister, Kerry, had been playmates from the Pacific Palisades. They had lived directly across the street from me, on the corner of Miami Way and El Medio Avenue.

Meeting up with someone from my past, whom I, coincidentally, bump into somewhere across the globe, has happened on several occasions. I always find the experience astounding. What are the statistical odds of accidentally crossing paths with your six-year-old playmate while 6,094 miles away from home? It always makes me wonder if there is some divine plan that is guiding my life. As I waited for a glimmer of recognition from her, I asked myself: What does Wally have to teach me?

She had rented a house on the island for the summer and, for the week that Pitou and I spent there, we saw her just about every day. Spending time with someone my age, already a mother for seven years, deeply affected me. While I was the one experiencing the feminist’s dream of career advancement in a man’s world, her life centered completely upon her little girl, Paula—and she was happy. We dined together, got stoned together, and laughed together about our privileged childhood years in a Fifties world of convertible Chevy Impalas, Pepsi “for those who think young,” and mothers decked out in wooden Rockabilly shoes.

She had rented a house on the island for the summer and, for the week that Pitou and I spent there, we saw her just about every day. Spending time with someone my age, already a mother for seven years, deeply affected me. While I was the one experiencing the feminist’s dream of career advancement in a man’s world, her life centered completely upon her little girl, Paula—and she was happy. We dined together, got stoned together, and laughed together about our privileged childhood years in a Fifties world of convertible Chevy Impalas, Pepsi “for those who think young,” and mothers decked out in wooden Rockabilly shoes.

Towards the end of the summer, she and her blonde haired vixen boarded a boat destined for Italy. Passenger ships docked in the heart of the Old Town by the Adosado and Levante quays.

Waving to me from the aft deck as I stood on the pier watching her departure, the blast of the ship’s horn bellowed its low, pulsating groan. I haven’t seen Wally since, but I believe she came into my life that summer with a purpose—a message, intimately written for me. After she left, I stopped using birth control.

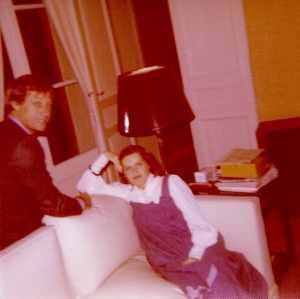

A year had passed since then. Sitting in a sofa overlooking le Champ de Mars, I was now three months pregnant. Pitou had lowered the window awnings to keep the apartment cool. A soft summer light infiltrated the living room, leaving an orange glow as it passed through the canvas of the tangelo-tinted shades. My feet were swollen from the heat and I was already putting on weight. The doctor had told me to eat to my heart’s content, to not deprive the baby of nourishment, advice that I willingly respected. It was late in the afternoon and, although I had lunched magnificently no more than three hours earlier, there was a tray on the coffee table, spattered with cheese rinds and breadcrumbs and a crock of beurre d’Isigny. It was the one time in my life when I ate without guilt; Camembert, Brie de Meaux, Pont l’Évêque and Reblochon, I smothered broken off pieces of the baguette our butler, Fahrid, brought into the kitchen each morning after shopping for the day’s meals on the rue Cler. Back then in France, there were none of the

A year had passed since then. Sitting in a sofa overlooking le Champ de Mars, I was now three months pregnant. Pitou had lowered the window awnings to keep the apartment cool. A soft summer light infiltrated the living room, leaving an orange glow as it passed through the canvas of the tangelo-tinted shades. My feet were swollen from the heat and I was already putting on weight. The doctor had told me to eat to my heart’s content, to not deprive the baby of nourishment, advice that I willingly respected. It was late in the afternoon and, although I had lunched magnificently no more than three hours earlier, there was a tray on the coffee table, spattered with cheese rinds and breadcrumbs and a crock of beurre d’Isigny. It was the one time in my life when I ate without guilt; Camembert, Brie de Meaux, Pont l’Évêque and Reblochon, I smothered broken off pieces of the baguette our butler, Fahrid, brought into the kitchen each morning after shopping for the day’s meals on the rue Cler. Back then in France, there were none of the  stigmas associated with drinking wine when pregnant, and my only friends who made mention of the taboo were American. Having witnessed the machinations of economic research analysts on Wall Street, intent on proving corporate points of view irrespective of their validity, I had come to regard the weight of statistical evidence with suspicion. Rather than listening to the gurus of medical science, I decided to listen to my body, giving it everything it craved. Interestingly, it never craved any one thing for long; and, every once in a while, I treated myself to a glass of good red.

stigmas associated with drinking wine when pregnant, and my only friends who made mention of the taboo were American. Having witnessed the machinations of economic research analysts on Wall Street, intent on proving corporate points of view irrespective of their validity, I had come to regard the weight of statistical evidence with suspicion. Rather than listening to the gurus of medical science, I decided to listen to my body, giving it everything it craved. Interestingly, it never craved any one thing for long; and, every once in a while, I treated myself to a glass of good red.

Eileen and Jerry, and Katie: the early days

That afternoon I had needed it. We had guests. Eileen Ford was in town with her daughter, Katie, and her old friend and West Coast associate, Nina Blanchard: the gruff voiced, chain-smoking maven of fashion who had turned Cheryl Tiegs and Christie Brinkley into household names. Eileen, of course, along with her husband Jerry, was the founder of what had become one of the most prestigious modeling agencies in the world: Ford Models. She had known Pitou for decades and never failed to call him when in Paris. He liked Eileen. But that didn’t stop him from seeing her, clearly, for who she was.

That afternoon I had needed it. We had guests. Eileen Ford was in town with her daughter, Katie, and her old friend and West Coast associate, Nina Blanchard: the gruff voiced, chain-smoking maven of fashion who had turned Cheryl Tiegs and Christie Brinkley into household names. Eileen, of course, along with her husband Jerry, was the founder of what had become one of the most prestigious modeling agencies in the world: Ford Models. She had known Pitou for decades and never failed to call him when in Paris. He liked Eileen. But that didn’t stop him from seeing her, clearly, for who she was.

“She remembers things as she wants to,” Pitou remarked to me shortly before her visit. “Rarely as they actually occurred.”

In November of 1970, Life magazine had referred to her as “the godmother of modeling. ” By that time, Pitou had already known her for close to twenty years.

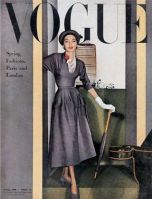

Legend has it that Eileen had agreed to sign Suzy only upon the condition that her older sister, Dorian Leigh, came with her. The package deal helped place the then, budding, Ford agency on the map. By 1947, Dorian had already appeared on some six Vogue covers, and she represented a prime catch for Eileen and her partner-husband, Jerry. Nonetheless, the Fords were unprepared for their first encounter with Dorian’s baby sister.

Legend has it that Eileen had agreed to sign Suzy only upon the condition that her older sister, Dorian Leigh, came with her. The package deal helped place the then, budding, Ford agency on the map. By 1947, Dorian had already appeared on some six Vogue covers, and she represented a prime catch for Eileen and her partner-husband, Jerry. Nonetheless, the Fords were unprepared for their first encounter with Dorian’s baby sister.

They met at a restaurant on Lexington Avenue, “a dump,” according to Suzy. She was very tall, with carrot red hair and a large frame by, then, fashion standards. And while Suzy would later explain, in numerous interviews once established as the Fifties Era super-model, that Eileen and Jerry “saw the possibilities of my being a model—No question,” Pitou remembered it differently. According to his conversations with Suzy, while she was still a teenager, Eileen Ford initially saw no possibility of her becoming a model and only humored Suzy for the sake of snaring Dorian.

. . .and Suzy, 1947

With my swollen feet resting on the lacquered coffee table, I thought about Suzy’s early troubles and how, ironically, twenty-nine years later, Georgia was suffering the same treatment from Eileen.

She was spending a few weeks with us in Paris. Her mother may have been vengeful. But no one could accuse her of being impractical. Georgia had just finished her junior year of high school and had applied to Harvard, Princeton, Yale and I’ve forgotten the trailing Ivy League institutions that completed her list of suitable college prospects. The point being that all of them cost a fortune; and with that understanding, suddenly, Suzy had come to recognize Pitou as Georgia’s father. He had stars in his eyes that summer, as he came to know the sixteen-year-old daughter he had last seen at the age of three. Confident and insecure at the same time, I watched as Georgia tried to make up for her lost years with her father by impressing him with her love of classical music, her appreciation of Einstein’s theory of relativity, and a bevy of other topics of interest, understandably, meant to impress. She wanted to make a bit of pocket-money to stash away for the college years. Given her mother’s history, modeling seemed like a pretty good bet. And it just happened that Eileen was in Paris.

Their lieu de rencontre that day had been our apartment, where I watched as Madame Ford sipped away at a ’68 Beune Premier Cru while telling Georgia that she didn’t have a hope in hell of ever becoming a model. No sooner had Eileen left that afternoon than Georgiabelle Florian Coco Chanel Thoreau de la Salle was on the phone to her mother in California.

“Don’t listen to a word she tells you!” Suzy bellowed to her still impressionable young daughter. “That’s EXACTLY what Eileen told ME at your age!” With tears streaming down her cheeks, Georgia tried to take comfort in her mother’s words.

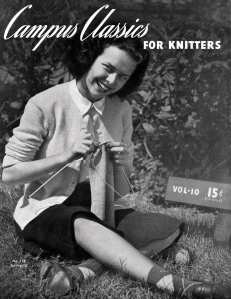

The Parker fury didn’t surprise me; they were known for blowing their tops when they didn’t get their way. But, what did surprise me was Eileen’s zeal. She seemed to take a perverse pleasure in dashing Georgia’s hopes. Back in the late Forties, she, too, had tried her hand at modeling. Failing abysmally—her only claim to fame was a cover for “Campus Classics for Knitters”—one couldn’t help but wonder if Eileen Ford, sadistically, made a point of striking back for having been brutally hurt herself long ago.

The Parker fury didn’t surprise me; they were known for blowing their tops when they didn’t get their way. But, what did surprise me was Eileen’s zeal. She seemed to take a perverse pleasure in dashing Georgia’s hopes. Back in the late Forties, she, too, had tried her hand at modeling. Failing abysmally—her only claim to fame was a cover for “Campus Classics for Knitters”—one couldn’t help but wonder if Eileen Ford, sadistically, made a point of striking back for having been brutally hurt herself long ago.

“It’s simply horrendous,” she remarked to Pitou the next day, while lunching with us on the Place du Marché Saint-Honoré at L’Absinthe, “Suzy’s attempt to re-live her youth vicariously through her daughter.”

She was a hard woman to get close to, Eileen Ford; a woman with a flash for a smile that hit you out of nowhere like lightning, only to disappear just as quickly—her white teeth gleaming for a split second as if escaping from prison.

“Jerry est un ange,” Pitou often remarked, while purposefully refraining from commenting on Eileen.

Feeling his daughter’s angst, he set out to distract Georgia by arranging for a weekend excursion to Bordeaux. We had a standing invitation from Catherine Hennessy to spend as much time as we wanted at her home overlooking the Bay of Biscay. She was never in the city during the summer months, preferring to care for her two children, Isabelle and Diego, at her cliff side maison d’été while her husband, Eric de Lavandeyra, stayed in town to work the Paris Bourse. Catherine always appeared to me to be the picture of domestic happiness, raising her children with the attention to detail of a nineteenth century matron of la plus haute noblesse. She was obsessively caring; and yet, one morning, four years after we spent that weekend with her in Bordeaux, she would mysteriously disappear from her Parisian flat, taking only her handbag with her– abandoning her two children and husband of seven years.  A member of Le Grand Prieuré des Gaules and a Free Mason of high rank, the rumors surrounding Eric persist to this day. Some, who knew Catherine well, say that she fled her home of necessity, fearing for her life after he attempted to throw her from a high floor window. Others paint her as a drunk and a drug addict, who took off because she could no longer stand the constraints of her wealthy bourgeois existence. I have thought of her often over the years, while asking myself where the truth must lie. It is a difficult exercise; we always think we know our friends and yet, the inner mystery of every human is just that: a mystery.

A member of Le Grand Prieuré des Gaules and a Free Mason of high rank, the rumors surrounding Eric persist to this day. Some, who knew Catherine well, say that she fled her home of necessity, fearing for her life after he attempted to throw her from a high floor window. Others paint her as a drunk and a drug addict, who took off because she could no longer stand the constraints of her wealthy bourgeois existence. I have thought of her often over the years, while asking myself where the truth must lie. It is a difficult exercise; we always think we know our friends and yet, the inner mystery of every human is just that: a mystery.

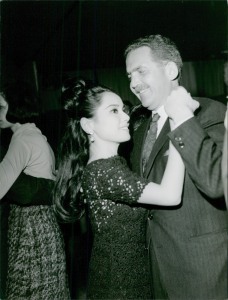

Laforet, with Maurice Ronet in “Plein Soleil”

Still, my experience of Catherine was of a woman grounded in sensibility–a woman who, in the six years I knew her, I never once saw drunk; a woman imbued with the cordial and polite airs that testified to her breeding, who spoke eloquently and intelligently and always with compassion and common sense. Disturbingly, Eric would shortly remarry, this time to the beautiful French actress and singer, Marie Laforêt, who, in 1994, created a national scandal by publicly accusing her husband of attempting to kill her.

As we drove to Catherine Hennessey’s home on the southwest coast of France that summer of 1976, if I had been given a glimpse into the future, I would have chalked it off as a hallucination.

“You can do anything you set your mind to,” Pitou told Georgia, as we drove. “Don’t ever believe others; believe in yourself.”

Taking the advice, she would force Eileen Ford to eat her words for a second time. During the decade of the 1980s, Georgia would model in both the United States and Europe, appearing in many magazines—Vogue included—eventually becoming a Ford model.

Taking the advice, she would force Eileen Ford to eat her words for a second time. During the decade of the 1980s, Georgia would model in both the United States and Europe, appearing in many magazines—Vogue included—eventually becoming a Ford model.

Looking back at those years in Paris, they seem a contradiction in terms; a period of my life where I began to wake up to the truth of the world, to its true economic and political structure, while participating in a social façade that hides the reality of it. By choosing to represent Wall Street, in a city that attracts the richest of the rich, I had embraced a world of obscene wealth while subjecting myself to the painful study of how that wealth is obtained and maintained.

Jimmy Carter was about to win the Democratic nomination for President. Indonesian president and U.S. strongman, Suharto, had just annexed East Timor, murdering some eighty thousand civilians in the process. And I sat, each week, lunching at the Relais Plaza as Dewi Sukarno navigated its linen and silver laden tables, bestowing kisses upon the cheeks of fellow international jet setters as she mused about which chic spot she planned on spending the upcoming weekend. Her husband was overthrown by Suharto in a coup in 1967, a U.S. backed Army-initiated massacre wherein an estimated one million people were killed—the rivers in Java, Sumatra, and Bali so filled with bodies that the water turned red.

Of course, back home, the press lied to us about our participation in the purge. But, in Europe, the populace was more enlightened. Its journalists could actually get into print the facts and opinions that, systematically, were shredded stateside. While Americans were, naïvely, falling in love with the U.S. Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, his breathtaking mendacity and trickery was already the subject of conversation in educated European circles. The man behind Gerald Ford, dispensing with the lives of people like pawns on a chessboard, was secretly prompting Suharto to “hurry up and get on with it,” to quickly murder as many as necessary in East Timor, so that the U.S. could cement its control of the former Spice Islands.

Of course, back home, the press lied to us about our participation in the purge. But, in Europe, the populace was more enlightened. Its journalists could actually get into print the facts and opinions that, systematically, were shredded stateside. While Americans were, naïvely, falling in love with the U.S. Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, his breathtaking mendacity and trickery was already the subject of conversation in educated European circles. The man behind Gerald Ford, dispensing with the lives of people like pawns on a chessboard, was secretly prompting Suharto to “hurry up and get on with it,” to quickly murder as many as necessary in East Timor, so that the U.S. could cement its control of the former Spice Islands.

Meanwhile, the elegant, always impeccably dressed Dewi, widowed since 1970 from her leftist, romantic revolutionary-turned-autocrat husband, floated between apartments in Switzerland, France and the United States while living off the proceeds of her deposed husband’s siphoned funds, deposited at the institution that gave one instant membership to “the club”: la Banque Privée in Geneva.

There was something ghostly about this world—ghastly and ghostly. And yet, it was difficult not to enjoy—the glamour, the scintillating backdrop upon which these other worldly characters performed their daily routine of gossip while feasting on smoked salmon and mache, and deciding whom they would invite for cocktails that evening at the bar of the Georges V. Yet, having hovered over the Reuter’s machine each morning, my mind was torn by the realization that some of the worst massacres anywhere since World War II had financed many of them— carefully orchestrated, murderous “cleansings” that had brought the US-backed New Order regime to power in Indonesia much as others, similar in nature, had cemented control in Iran, Guatemala, Zaire, Ghana, Uruguay, Panama, Laos, Chile, Brazil and Argentina. And all for the same reason: so that a tight circle of oligarchs—a dictatorship of generals and oil tycoons, of political élite and powerbrokers—could flourish. If you lived in Paris long enough, and knew a few of the well-connected, you were sure to rub elbows with this close-knit fraternity of men whose shared goals of “helping third world economies to grow” only made the few people who sit at the top of the pyramid richer, while pushing those at the bottom still lower. They all belonged to the club—members who gave their business to Brown & Root, whose dollars traded daily upon the very desks I sat at in the Paris offices of Merrill Lynch.

Their promotion of capitalism had resulted in a world system that resembled medieval feudal Europe. The one thought that ran through my head as I watched world events unfold while observing how guilelessly they profiteered at the expense of mass misery, was the verse from Ecclesiastes borrowed by Shakespeare: “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.”

Their promotion of capitalism had resulted in a world system that resembled medieval feudal Europe. The one thought that ran through my head as I watched world events unfold while observing how guilelessly they profiteered at the expense of mass misery, was the verse from Ecclesiastes borrowed by Shakespeare: “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.”

It continued to dawn on me that everything I had been taught as a child was a lie, and that the pretended “end that justified the means” was always the same: to save the world from the domino effect of Communism by giving it Corporatocracy instead. Sukarno had headed the third largest Communist Party in the world, the PKI. And we were losing the battle in Vietnam, which made seducing Indonesia key as part of the U.S. plan to ensure American dominance in South East Asia. It was clear in Europe that Suharto would serve D.C. exactly as the Shah had in Iran, but not without expense. For the gains made in Indonesia would come at a serious cost—one that would have to be paid decades down the road when the repercussions of American Imperialism would begin to resonate throughout the Islāmic world.

Of course, the real incentive had nothing to do with the containment of the spread of communism and everything to do with the distribution of oil. Like Vietnam, Indonesia had oil, and the executives at Exxon were exuberant over the possibilities. Once richly exploited for its spices, colonial marauders had returned to rip up Indonesia’s 17,000 islands, this time, for its black gold—with Nicaragua, Yugoslavia, Haiti, Honduras, the Philippines, Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran and Syria still to come.

Of course, the real incentive had nothing to do with the containment of the spread of communism and everything to do with the distribution of oil. Like Vietnam, Indonesia had oil, and the executives at Exxon were exuberant over the possibilities. Once richly exploited for its spices, colonial marauders had returned to rip up Indonesia’s 17,000 islands, this time, for its black gold—with Nicaragua, Yugoslavia, Haiti, Honduras, the Philippines, Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran and Syria still to come.

As the nature of U.S. foreign policy became more clear to me, I found refuge in a vie quotidienne that was increasingly domestic. Escape; my idea of an ideal weekend was roaming through the aisles at Dehillerin in search of the perfect French paring knife, followed by tea and cucumber sandwiches at Carette. I sought sanity in the simple things. In the evenings, Pitou and I would cook a pot au feu for friends who dined with us in the kitchen over bottles of Beaujolais. Life was utterly bourgeois; in short, everything you want it to be, provided that its being lived with the one you love. I was so completely happy that the prospect of a night out on the town had almost become a bore. And yet, the opportunities never ceased.

Shortly before leaving for LA, where I planned to give birth, thus bestowing dual nationality upon our child, Gerard Bonnet visited my desk at Merrill.

Shortly before leaving for LA, where I planned to give birth, thus bestowing dual nationality upon our child, Gerard Bonnet visited my desk at Merrill.

“Qu-est-ce que vous faites demain soir?” he asked.

“Pas grandes choses. Pour quoi?” [2]

He was prospecting the Maharani Sita Devi Shahib of Baroda—the glamorous and once strikingly beautiful widow of the last ruling Maharaja of Baroda, a charming spendthrift who, although worth some 300 million dollars in 1939, had a reputation for keeping his fingers in the state’s money pot. One of India’s wealthiest royal families, the Gaekwads of Baroda controlled their own army and navy from the Laxmi Vilas Palace, an imposing country house believed to be four times the size of the Queen of England’s royal residence at Buckingham. Known for their love of luxury, they lived in lavish style, acquiring legendary objets d’art.  The Pearl Carpet of Baroda, decorated with thousands of Basra pearls, rubies, and turquoise—an exceptional 19th century revival of the fabled carpets from The Thousand and One Nights, along with the magnificent 128-carat “Star of the South” diamond—one of the largest in the world, were among the pieces in the Maharani Sita Devi’s personal collection brought with her when she moved to Monaco in 1946.

The Pearl Carpet of Baroda, decorated with thousands of Basra pearls, rubies, and turquoise—an exceptional 19th century revival of the fabled carpets from The Thousand and One Nights, along with the magnificent 128-carat “Star of the South” diamond—one of the largest in the world, were among the pieces in the Maharani Sita Devi’s personal collection brought with her when she moved to Monaco in 1946.

The Maharani’s son, Prince Sayaji Rao Gaekwad of Baroda, better known as Princie, had recently turned thirty and was proving a constant source of worry and concern for his mother. Unmarried and sans profession, she had placed a call to her old friend, Gerard, to see if he could somehow interest Princie in the ways of Wall Street. And what better place to find out than while dining at Maxim’s—on Merrill’s tab.

“Voulez vous venir?” [3] Gerard asked.

I could never turn down an invitation to Maxim’s. The Art Nouveau restaurant, where no respectable woman of the late nineteenth century would have deigned to be seen, once served as the chic watering hole of wealthy Parisian gentlemen and their mistresses—courtesans whose taste dictated fashion, women like Mata Hari, la Belle Otéro and Cléo de Mérode—les grandes horizontals of their era who served as the trophy companions of powerful men, as well as their hostesses and artistic muses. And nowhere were they more often seen than at Maxim’s.

An evening chez Maxim’s is always one of enchantment. Its elegant interiors, inspired by the fauna and flora of poppies, and dragonflies, butterflies and birds, banished angles and straight lines in favor of shapes that wrap and entangle.

An evening chez Maxim’s is always one of enchantment. Its elegant interiors, inspired by the fauna and flora of poppies, and dragonflies, butterflies and birds, banished angles and straight lines in favor of shapes that wrap and entangle.

By accepting Gerard’s invitation, I knew I’d be doing him a favor. He was methodical, reasoning that Pitou would keep the Maharani laughing while I, the only one close to Princie’s age, might be able to spark the young man’s interest in a respectable career in finance.

Gerard was always given a prime table everywhere he went, and the night we dined Chez Maxim’s was no exception. On the banquette in the main dining room—a spot from which we could leisurely sip our champagne while the house violinists moved from table to table, we watched the comings and goings of the highly fashionable. You could hear a pin drop as Marisa Berenson entered the room, dressed to the nines while peering mysteriously through the black lace of her veiled velvet hat. I have always found it amusing to watch the expression on the face of a woman, once known as a showstopper, as her successor takes center stage. And that evening, the Maharani did not disappoint. Known for her flamboyance and love of fine jewels, her beauty had faded long ago; and as Marisa sailed past us, smiling at Pitou whom she’d known since her childhood, Sita Devi’s eyes spoke of her pain. I caught the audible sigh that emanated from her throat as she consoled herself with generous servings of Beluga. Smothering her toast with chopped onions, she heaped it with black caviar spooned with a ladle from the crystal bowl that was planted in front of her. I don’t remember any of the conversation that evening. But I can still hear the Maharani munching as she grinned at Pitou, knowing that her dwindling assets were not at risk for the bill that night. When l’addition arrived, Gerard gave me his signature he-he laugh. It was over five hundred dollars—an absolute fortune in 1976 that represents some three thousand dollars today. As for Princie, I knew within five minutes of meeting him that a career in finance was not for him. Already an alcoholic, with too much money and free time on his hands, nothing seemed to interest the young man.

A chauffeured white Rolls Royce waited for them, curbside, on the rue Royale. Gerard gave the Maharani a kiss on both cheeks before helping her into its plush interior. Ten years later, Princie would end his life by slitting his throat with a kitchen knife. We think that struggle is the bane of existence. Yet, I believe it is what saves us.

The number of times I would be forced to recognize this seemingly contradictory fact are too numerous to mention. Yet, because of Pitou’s past—his association with so many of the twentieth century’s rich and famous—I was left without a doubt.

“Be careful what you wish for,” he often remarked, never bothering to finish the popular adage.

Riding on the coat tails of his life, he would prove the truism to me, time and time again.

In late July, we left for LA. I was due at the end of December and we still hadn’t arrived at names for the baby that Pitou and I both liked. After two thousand suggestions, we had nothing in the event of a boy. And only Charlotte had emerged as a possibility for a girl, although I was luke-warm on that one. Finally, in frustration, I picked up a copy of Standard and Poor’s stock guide and began thumbing through the names of corporations.

“What about Devon?” I asked one morning, spotting Devon Inc. among the D listings.

Pitou’s eyes lit up immediately.

Pitou’s eyes lit up immediately.

“I like it,” he said.

Closing the index, I heaved a sigh of relief and resolved to give birth to a girl.

Returning to my roots after five years in Paris, I was sure that I was more French than American—a feeling that has never really left me, even after three decades of living back in the States. Paris changed me. Or, perhaps, it just reminded me of an existence I have already known, in a past life. It has often struck me that my name—Bérénice—is used more frequently in France than any other country in the world. And that only the French seem to know how to pronounce it correctly. Once back stateside, I couldn’t deny a feeling of isolation, of separation from my true roots. It scared my mother, saddened her. I didn’t like seeing this; I was close to Mom. I had a strong, protective instinct for her that had always resulted in my wanting to spare her any pain. And, of her three children, I was the one who took care of her, who saw to it that her bills were paid, that her car ran properly, and that her medical insurance and property taxes were covered each year. Washing the breakfast dishes as I planned the modest wedding ceremony that, both, Pitou and I wished for, she lamented: “You’ve changed.”

She had a look on her face that I knew too well. Even with her back turned to me, as she stared through the window above the kitchen sink overlooking Miami Way, I could see it, feel it. It was the look that she got when she was experiencing loss; the look that came over her when she thought about my father’s death, and everything that had meant to her for the rest of her life—a look of sorrow mixed with resignation that a friend of hers had once caught while she was Marlin fishing off the coast of Baja. She no longer recognized me.

Born to wealthy Mexican landowners, with extensive cattle ranching interests in the state of Durango, she had been deprived of the benefits when her parents were subjected to the banditry of Pancho Villa. Fleeing for their lives, they re-settled in East LA–with nothing more than the shirts on their backs. Of my maternal grandparents’ six children, my mother was the most beautiful, inheriting the magnetism of mi abuelo–the deep brown eyes one got lost in, the flared nostrils that, to me, seemed to breed fire–and the grace of mi abuela, whose strength and dignity only increased with age. More Spanish in appearance than Indian, more European than American, my mother had lost all title to her family’s fortune. But their proud nobility persevered in her face. Perhaps, because of this, her reaction to my transformation, my wholehearted embrace of everything Occidental, came as a surprise to me.

Born to wealthy Mexican landowners, with extensive cattle ranching interests in the state of Durango, she had been deprived of the benefits when her parents were subjected to the banditry of Pancho Villa. Fleeing for their lives, they re-settled in East LA–with nothing more than the shirts on their backs. Of my maternal grandparents’ six children, my mother was the most beautiful, inheriting the magnetism of mi abuelo–the deep brown eyes one got lost in, the flared nostrils that, to me, seemed to breed fire–and the grace of mi abuela, whose strength and dignity only increased with age. More Spanish in appearance than Indian, more European than American, my mother had lost all title to her family’s fortune. But their proud nobility persevered in her face. Perhaps, because of this, her reaction to my transformation, my wholehearted embrace of everything Occidental, came as a surprise to me.

To a certain extent, my mother was right. I was not the young American girl who had left her in the summer of 1971. My sister, Inez, used my metamorphosis as an excuse to distance herself further from a sibling whom she had found annoying for many years. Her disdain for my Parisian interests, my newfound international viewpoint, dripped from the frown on her face that, persistently, greeted me. We had been inseparable as young children, with me affectionately referring to her as “Nechie,” and she, trailing after the big sister whose name she could only pronounce as “Boonie.” Even then, I remember thinking that I was different; that, somehow, I didn’t fit anywhere. Not in my family, not at school among my classmates—not anywhere. And so, it came as no surprise that, when I finally felt that I had found my true home, with Pitou, it and he would be rejected by all who had come before him.

My family disliked Pitou intensely, with only my brother, Martin, giving him half a chance. At first, I deluded myself with the belief that it was because of our difference in age and that, with time, they would come to love him as I did. But there was so much more going on; a fundamental revulsion between them, of life philosophies, of tastes, of affinities, that deep down inside of me I knew could never be reconciled.

“Ce n’est pas mon monde,” [4] Pitou would tell me. A truth that created so much pain yet, nevertheless, compelled me to accept the fact that I would have to choose between them, or risk losing the love of my life. Strange thoughts came to me as I wrestled with their differences. In the end, it’s the little things that separate us. Inez had visited me in Paris while Pitou and I were still living on the avenue Foch. I was working late, the day she arrived—a shift that obliged me to stay at the office until nine at night when the markets in New York closed.

“Don’t worry,” Pitou told me. “I’ll pick her up at the airport.”

It was her first time in Paris—in Europe, for that matter. And as they circled the Porte Dauphine in Pitou’s mini-cooper, headed for our apartment on the corner of the Avenue Malakoff, the evening lights that kept the Arc de Triomphe awash in gold glistened before them. It is a magnificent sight the first time encountered, one that I will never forget. And Pitou had specifically chosen his route in order to surprise Inez with the beauty of it.

It was her first time in Paris—in Europe, for that matter. And as they circled the Porte Dauphine in Pitou’s mini-cooper, headed for our apartment on the corner of the Avenue Malakoff, the evening lights that kept the Arc de Triomphe awash in gold glistened before them. It is a magnificent sight the first time encountered, one that I will never forget. And Pitou had specifically chosen his route in order to surprise Inez with the beauty of it.

“Oh my God,” she exclaimed, as they barreled up the cobblestoned avenue Foch. “There are no lane lines on the street!”

The pedantic response to the beauty of Paris struck Pitou—a tiny sign of an impossible gap—a lack of understanding that would grow over time, separating them forever.

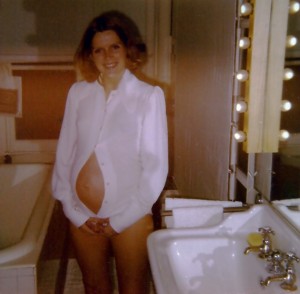

We married on the 21st of August—five years to the day of my arrival on the tarmac of Orly with Debbie. Only my family was present at the wedding. Pitou, in his inimitable style, arrived at the small chapel I had chosen for our nuptials dressed, head to toe, in solid white, while I, now five months pregnant, stood before him in Laura Ashley blue. He laughed a laugh of pure joy as I turned to him at the altar. And, while taking my vows to love and honor him—for richer, for poorer, for better, for worse, in sickness and in health, ‘til death do us part, my Uncle Oscar looked on with his impish grin that he had kept since childhood, his “I told you so” smile, while snickering as only he knew how.

The days that followed were laborious. I was gaining weight quickly, and looking like an elephant disagreed with me. The little soul I was carrying would weigh in at seven pounds; and yet, I had managed to gain thirty. The only thing I felt like doing was watch television. In the study of the house in the Palisades bought by my grandmother, Berenice, Pitou would straddle me with his legs, wrap his arms around my belly, and wait for the baby to kick.

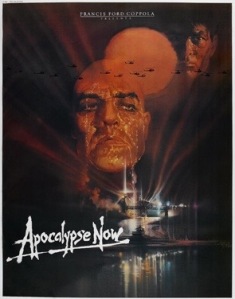

Christian Marquand was in town, about to leave for the Philippines with Marlon Brando to shoot “Apocalypse Now.” Whenever in LA, you could find Christian up on Mulholland where he had a standing invitation to stay at “Marloo’s.” It was the nickname that he and Pitou had given to Brando when they first met him in Paris back in the early Fifties, before Marlon had become a household name. Brando had been noticed by the Mille brothers while hanging out on the boulevard Saint Germain. His animal chic had quickly gained him access to Gerard Mille’s world of lunches with Cocteau and Chanel, Serge Lifar and Andre Malreaux—a world that Brando seamlessly integrated as an unknown, a nobody, but with that unmistakable presence of mind that was about to differentiate him from the masses. Pitou and Christian picked up on it quickly, incorporating him into their social circle before the world ever knew who he was to become. And the friendship lasted for the rest of their lives.

One evening in late November, when I was feeling particularly lethargic, with all of the despondency that state entails, Pitou announced that we would be spending the evening out.

“Where?” I asked.

“It’s a surprise,” he answered.

We hopped into my mother’s ’68 Buick Riviera, and headed north. When Pitou turned off the 405 for 12900 Mulholland Drive, I figured he was heading for Jack Nicholson’s house—a place we had visited with Christian during the days when Nicholson and Angelica Huston were still a number. Swimming in this ultra Hollywood environment, it had hit me how truly bourgeois I had become while living in France. I loved running a household, preparing for dinner parties, creating menus, buying linens and always making sure there were flowers with exotic scents that filled the rooms. Maitress de maison was a job that suited me, one I thoroughly enjoyed. But, here, in Hollywoodland, such trivial pursuits were delegated, not to the woman of the house, but to a good friend in need of the bucks. Helena Kallianiotes, the Greek-American actress known for her portrayal as the ultra-aggressive roller derby skater, Jackie Burdette, in “The Kansas City Bomber” was the impresario of Nicholson’s life: the woman behind the scenes who saw to its flawless assimilation by taking care of the mundane details Nicholson had neither the time nor the patience for. Invariably, she was the one who would greet you at his door.

We hopped into my mother’s ’68 Buick Riviera, and headed north. When Pitou turned off the 405 for 12900 Mulholland Drive, I figured he was heading for Jack Nicholson’s house—a place we had visited with Christian during the days when Nicholson and Angelica Huston were still a number. Swimming in this ultra Hollywood environment, it had hit me how truly bourgeois I had become while living in France. I loved running a household, preparing for dinner parties, creating menus, buying linens and always making sure there were flowers with exotic scents that filled the rooms. Maitress de maison was a job that suited me, one I thoroughly enjoyed. But, here, in Hollywoodland, such trivial pursuits were delegated, not to the woman of the house, but to a good friend in need of the bucks. Helena Kallianiotes, the Greek-American actress known for her portrayal as the ultra-aggressive roller derby skater, Jackie Burdette, in “The Kansas City Bomber” was the impresario of Nicholson’s life: the woman behind the scenes who saw to its flawless assimilation by taking care of the mundane details Nicholson had neither the time nor the patience for. Invariably, she was the one who would greet you at his door.

But, that night, Pitou passed Jack’s house and, instead, headed up the hill to a second property that dominated the landscape. Heavy like a whale, I could barely get out of the car. The doors of the Riviera weighed a ton, and rather than battling them, I waited for Pitou to forklift me from the shotgun seat. The house we approached was a modern one-story structure, with lots of glass. Built sometime in the late Fifties, I guessed, the vegetation surrounding it was rich. Pitou didn’t knock. He’d been here before. Leading me through the entrance hall, we arrived in a large family room next to the kitchen. Christian was seated on the sofa, in jeans and a cotton shirt, putting his socks on, the clothes from his open suitcase spread across the floor. Seeing me, he laughed.

“You’re as big as a house,” he joked.

Over the years, I had become very close to Christian. He was a constant fixture in our lives, dining with us frequently, traveling with us on our annual ski vacations to Val d’Isere and Meribel, and dropping in on us, regularly, for no other reason than to chat. Le bavardage was the glue that had bound him and Pitou together since childhood.

Other than the television set, conspicuously humming in the background, the house was quiet.

“You want something to drink?” Asked Christian.

Without waiting for my response he began walking toward the kitchen. Just as he did, I heard the front door open and slam shut.

He hadn’t yet shaved his head for his role as Colonel Kurtz. And, although aging and overweight, the sex appeal that had made him a star twenty-five years earlier was still apparent. Marlon Brando didn’t just enter a room. He occupied it—all of it. The sincere joy, the surprise upon finding Pitou in his home, was magnanimous. He literally vibrated with warmth, and hugging my husband, I noticed tears of pure joy in his eyes.

He hadn’t yet shaved his head for his role as Colonel Kurtz. And, although aging and overweight, the sex appeal that had made him a star twenty-five years earlier was still apparent. Marlon Brando didn’t just enter a room. He occupied it—all of it. The sincere joy, the surprise upon finding Pitou in his home, was magnanimous. He literally vibrated with warmth, and hugging my husband, I noticed tears of pure joy in his eyes.

“Marloo,” Pitou said, while still holding Brando’s shoulders, “this is my wife, Bérénice.”

Turning to me, Brando gave me that grin, the one from “On the Waterfront,” when he’s rapping with Rod Steiger in the back of a cab about how he could have been “a contender. “

Turning to me, Brando gave me that grin, the one from “On the Waterfront,” when he’s rapping with Rod Steiger in the back of a cab about how he could have been “a contender. “

He grabbed me in a bear hug, before exclaiming: “If you are Pitou’s wife, then you are my friend.”

And I could see in his eyes that he meant it, that the tie he shared with his old friend was something he truly prized. It was as if he was saying to me “if Pitou chose you, then you must be special.”

We spent the next few hours drinking Cokes and eating cheese while seated in Marlon’s round, tufted, kitchen banquette. They spoke of old friends, of their times in Paris when they wore turtle neck sweaters to avoid having to pay for their shirts being washed and ironed. And, at one point in the evening, Brando asked about Suzy—but only briefly, sensitive to not make me feel the outsider to their circle of camaraderie.

“Why don’t you come to Tetiaroa?” Brando asked, referring to his island in French Polynesia that he had first set eyes upon while filming “Mutiny on the Bounty.” “There’s a room waiting for you.”

“One day,” Pitou responded.

Yet I knew he would never go.

Knowing of their early friendship, I, too, had wondered why Pitou never saw Marlon. He loved Marloo, but he knew him too well.

“You have no idea how demanding he can be,” Pitou told me. “He doesn’t sleep, which means that, in his presence, you won’t either. He’ll keep you up all night long, so that he can unburden himself of his thoughts. He’ll talk until you fall off your chair and then wake you up again so that he can talk some more. It’s exhausting, but he’s so used to being the center of attention that it’s incomprehensible if you aren’t willing to be there for him.

“Je ne peux pas, mon chou. Je t’en prie. Ne me demande pas ça.”[5]

Pitou’s history of Brando went back before the heart-throb had filmed “A Streetcar Named Desire.” A theatre actor by profession, he had not yet achieved full star power, although looking at him, you had to wonder why. In the film credits, producer Charles Feldman had billed him under Vivian Leigh. It was the last time Brando would ever end up with second billing. Tennessee William’s classic would catapult him into a rarefied plane of existence, as well as bring him an Academy Award for Best Actor for his sexy, brutal and endlessly fascinating portrayal of Stanley Kowalski. But, back then, he was still relatively unknown. A stage actor by preference, he had only starred in one other movie role: that of Ken Wilcheck, a World War II vet paralyzed from the waist down by a gunshot wound in Fred Zinneman’s 1950 film, “The Men.”

He liked to say that one’s associations were nothing more than a function of one’s affinities and, with that in mind, had promptly adopted Christian and Pitou as his soul brothers. Brando didn’t need much: two good friends, wood for the fireplace, and he was happy. Lee Strasberg, the renowned artistic director for the Actor’s Studio, once commented that the two greatest acting talents he had ever worked with were Marilyn Monroe and Marlon. Yet, ironically, even back in the mid Fifties, Brando didn’t think much of acting. He had often been quoted as saying that the only reason he was in Hollywood was because he didn’t have the moral courage to refuse the money. Marlon had expressed it a bit differently to me.

“I do it,” he said, “not because of some burning passion, but because it’s the only thing I know how to do.”

Pitou’s nickname for him, “Marloo,” surprised people who didn’t know him well. Marloo was nothing like the characters for which he had become famous: the brash, insensitive Kowalski, the tough rebel on a motorcycle, Johnny Strabler, Brando hated the arrogance and unwarranted confidence of these creatures; they scared him. Instead, he, Christian and Pitou, were quiet, introspective men who in many ways epitomized Castiglione’s ideal male. They were men who believed that the style is the man and, by style, I do not mean dress. It was important to be polite, to express oneself accurately and elegantly, and to be attentive to women. They accepted people as they were, tolerantly and compassionately and, above all, without judging them. But most endearingly, they laughed as quickly at themselves as they did at others. There was an easy, natural manner about these three that left them in command of every situation and, because of their shared qualities, kept them the best of friends all of their lives.

Pitou considered himself to be a humanist; he distrusted people who, claiming to hold the truth, sought to orchestrate the world in line with their view of it. Defiant of imposed order, be it political, religious or just societal, he questioned the rules of others while remaining unconcerned as they followed them. He rejected the notions of sin and guilt—especially as they pertained to sex—valued the principles of l’amour courtoise, while adhering to a philosophy of the here and now. And I believe that, because of this, he counted Christian and Marlon among his true friends. There was an unspoken bond between these three, one that allowed them to pick up where they had last left off as if they had seen each other just the other day; even if years had passed in the interim.

We spent a quiet Christmas with my mother. I could no longer sleep at night. When on my back, the weight of the baby pushed on my diaphragm, making it difficult for me to breathe. But, when on my side, she would kick like crazy.

The day after Christmas, Ron McCloud gave Pitou a call. He had been seeing Inez just long enough for us to get to know him. Tall and lean with a grin that wouldn’t quit, he was, without a doubt, the best looking boyfriend she ever had. He was also the only one possessed of an inborn, natural chic. A magnanimous personality, Ron made friends instantly, always knew the best places to dine, where to get the best deals in town, and how to dress with that casual elegance that appeared effortless, although it never is. Pitou adored the guy.

He had just moved into a guesthouse in Malibu overlooking the Pacific.

“Can you come for lunch?” he asked.

“Yeah, sure!” Pitou replied.

We brought my mother along but I don’t remember Inez being there and think that she and Ron must have, already, been drifting apart.

That day, we spent the entire afternoon with him. There was a December breeze, touched by the warmth of Santa Ana winds. The blue water off the coast glistened from the sun’s highlights and, looking at it, as my mother and Pitou read the LA Times, I knew that, one day, we would live in Malibu.

That day, we spent the entire afternoon with him. There was a December breeze, touched by the warmth of Santa Ana winds. The blue water off the coast glistened from the sun’s highlights and, looking at it, as my mother and Pitou read the LA Times, I knew that, one day, we would live in Malibu.

When we got back to the Palisades, I was exhausted. I went to bed early but woke up around eleven, drenched. At first, I thought I was just having a particularly bad episode of night sweats. But the sheets were saturated. My water had broken.

We got to Cedar Sinai around midnight. By that time, my labor was in full force. I thought, for sure, the baby would come quickly. But, after the physician administered an epidural, my labor stopped completely. . . for the next 18 hours. I slept most of the time, while Pitou paced the floor. And, when I awoke the next afternoon around 3:00, he looked a wreck. I can honestly say that our daughter’s birth took a greater toll on Pitou than on me.

We didn’t know if the baby was a boy or a girl. We didn’t want to know, preferring to experience that moment of surprise that no one, today, seems to opt for. My obstetrician, Marshall Kadner, was so concerned by the aborted labor that he was seriously considering a cesarean.

“NO!” I screamed. “My baby will be born naturally!”

My response shocked Marshall; but he, immediately, handed Pitou a pair of hospital greens before having me wheeled into the OR.

“Okay,” Kadner replied. “But, in that case, I am going to have to induce your labor.”

I told myself that I was going to be like one of those Japanese women who give birth without a scream. What a laugh. I raised the bloody roof. With me, in the operating room, Pitou held my hand the whole time I gave birth, while administering a wet wash cloth, with ice, from time to time to quench my thirst. I had no sensation of time, of when the baby would arrive, until the very second she decided to. She ripped me apart–the only moment of pain that I can still remember. But with her first cry, it disappeared. Marshall smiled.

“It’s a girl,” he said.

Cutting the umbilical cord, the first thing he did was to place the slimy little angel on my stomach. I couldn’t see Pitou’s smile. It was covered with a surgical mask. But I didn’t need to; I could see the joy in his eyes.

“Hello little Devon,” I whispered.

She immediately stopped crying, as if she recognized her name.

“Welcome to Earth.”

Pitou was covered in blood. It had spattered onto his hospital greens as Devon had entered the world. And just as he had saved the mini dress I was wearing on the day we first met, so did he wrap the coveralls he wore on the day he first met Devon. I still have them, unwashed, a testament to the deep affection—the love he felt for the both of us, and that incredible moment, suspended in time.

It was about then that I began to notice a change in Pitou. He was calmer than ever before, happier—at peace. Cosmopolitan by nature, it was clear to me that he was tiring of the stresses and strains of city life. The laid back easiness of California, of beach life at sunset, and parking without the bother of searching for a spot, appealed to him. He liked walking the streets in torn jeans and shoes without socks, and I could feel a wanting for a simpler life—especially now that we had brought a child into it. Paris was losing its luster—a fact that had me a bit in shock, being that he had always referred to LA as “Tahiti.”

And so I took the plunge and, using proceeds from trust funds left to me by my grandmother Berenice, bought a house on an acre of land on North Saltair Avenue in Brentwood. I told Pitou it was “just an investment,” and that I wasn’t trying to uproot him. But once escrow closed, I was astonished to find that he wanted to move in immediately.

We lived there for the next couple of months without furniture—other than a bed covered with Bill Blass sheets. It was bliss—the nothingness of empty rooms that looked out upon green lawn bordering our kidney-shaped swimming pool. We drank cocktails from frosted tumblers with red piped edges, bought at Bullocks-Westwood. I introduced him to my closest girl friends from Westlake; and we danced throughout the empty house to the sounds of “Let’s All Chant” and “Come Into My Heart” as I counted my blessings and thanked God for this exceptional man who had brought me joy and understanding, love and sensuality, all at once.

We lived there for the next couple of months without furniture—other than a bed covered with Bill Blass sheets. It was bliss—the nothingness of empty rooms that looked out upon green lawn bordering our kidney-shaped swimming pool. We drank cocktails from frosted tumblers with red piped edges, bought at Bullocks-Westwood. I introduced him to my closest girl friends from Westlake; and we danced throughout the empty house to the sounds of “Let’s All Chant” and “Come Into My Heart” as I counted my blessings and thanked God for this exceptional man who had brought me joy and understanding, love and sensuality, all at once.

A telegram from Ramiro broke the spell.

“When are you coming back?” he beseeched.

My career obligations at Merrill beckoned. And, regretfully, in the days that followed, we boarded the plane for Paris, with little Devon in toe, the circle complete.

[1] “Is she really pregnant?”

[2] “What are you doing tomorrow night?” he asked. “Not much. Why?”

[3] “Would you and Pitou like to come?”

[4] “Their world isn’t mine.”

[5] “I can’t, my darling. I beg you. Don’t ask that of me.”

Next Post: Paris- The Cinderella Years: “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby?”

Bravo! Well done, Berenice….can’t wait for the next episode…..

LikeLike

Bravo! Well done, Berenice! Can’t wait for the next episode…….

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOVED IT, Bernie!!!!!

Bisous,

Bonnie

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

Every post I read, every single one, sucks me in from the first word into this world of yours…. I cannot express how much I love your writing – you are brave, fierce and fearless, baring it all – it’s all there, the good, the less so, beautiful and the not so beautiful, so honest and un-sentimental (is that even a word???)… thank you…. I love your writing

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t tell you what comments like yours mean to me. I strive for raw honesty. Thank you, Samantha.

LikeLike

Tried to leave comment,it rejected my password. Too complicated,enjoyed reading all. Susan

Sent from my iPad

LikeLike

It seems you had a wonderful time writing this one. As if you were enjoying a fine beaujolais by the fireplace and reminiscing with a friend. Your revelations were open and honest to the bone. Thank you for letting us into the windows of your life … hope it is not too long before we get to Paris again!

LikeLike

The best post yet, giving me a real insight into your family!

LikeLike

I had a wonderful time reading some more about your magical life with Pitou. It’s so well written and just flows along. I just couldn’t put it down. Please continue as I can’t wait for the next episodes.

LikeLike