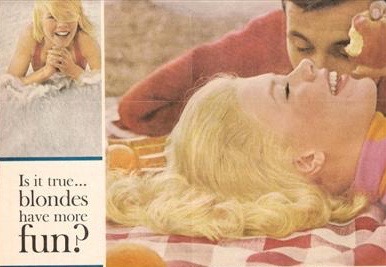

SHE WAS EVERYWHERE YOU LOOKED when I was thirteen: in Ship ‘n Shore and Lady Clairol ads, Bobbie Brooks and Jonathan Logan spreads, and on the covers of Ingenue and Seventeen Magazine. In 1965, she was the girl who made you believe that, yes, blondes do have more fun. If ever there was a face that represented “the California Girl,” it was Terry Reno’s.

SHE WAS EVERYWHERE YOU LOOKED when I was thirteen: in Ship ‘n Shore and Lady Clairol ads, Bobbie Brooks and Jonathan Logan spreads, and on the covers of Ingenue and Seventeen Magazine. In 1965, she was the girl who made you believe that, yes, blondes do have more fun. If ever there was a face that represented “the California Girl,” it was Terry Reno’s.

But, for me, more than anyone, she exemplified the reality of Six Degrees of Separation: that everyone and everything is just six or fewer steps away, by way of introduction, from any other person in the world. Vedas say that the earth is a family and everyone is connected to everyone else—a universal social connectivity that represents unity.

I was first “introduced” to Terry when in the eighth grade, while traveling to Westlake in the early morning carpools I shared with girls I had known since elementary school. Laura Ackard, Roxanne Harris and Mary Craddock became classmates of mine when my grandmother had enrolled my sister and me at an exclusive parochial school—Saint Matthew’s—in the Pacific Palisades. Now in our teens, but still in saddle shoes and rolled down cotton socks, with our notebooks on our laps, we squeezed into the back seats of our mothers’ station wagons each morning, as they made the thirty minute trek up Sunset Boulevard toward Holmby Hills.

I was first “introduced” to Terry when in the eighth grade, while traveling to Westlake in the early morning carpools I shared with girls I had known since elementary school. Laura Ackard, Roxanne Harris and Mary Craddock became classmates of mine when my grandmother had enrolled my sister and me at an exclusive parochial school—Saint Matthew’s—in the Pacific Palisades. Now in our teens, but still in saddle shoes and rolled down cotton socks, with our notebooks on our laps, we squeezed into the back seats of our mothers’ station wagons each morning, as they made the thirty minute trek up Sunset Boulevard toward Holmby Hills.

Roxie always had the latest edition of Seventeen, which she judiciously perused as Laura and Mary tried, in vain, to snatch it from her. I, the shy one of the group, caught glimpses of the preppy pages only as Roxie turned them.

“Oh, look at Colleen!” Laura exclaimed, referring to Terry’s brunette alter-ego and oft modeling companion, Colleen Corby.

“I think she’s the prettiest,” she added, as the Supremes wailed “Baby Love” over the car radio.

But I didn’t. While Laura, with her long chestnut-brown hair, sought to emulate Corby, I wanted to look just like Terry. Awkward, with steel braces on my teeth, I stared longingly at Reno’s photo spreads, while trying to imagine her daily life. Little did I know that, through her, I was but one degree away from my future husband. Barely pubescent, I was already dreaming of him, wondering where he was and what he was doing at that very moment. Years later, I would be given the answer.

He was in bed . . . with Terry.

For years, a picture of her, in profile, holding a wine glass to her chin, sat in the library shelves of Pitou’s flat on the avenue Foch. An autumnal baby, like Suzy and me, she, too, was a Scorpio—the girl who had bridged the ten-year gap between Pitou’s detachment from his first wife and his attachment to his second.

For years, a picture of her, in profile, holding a wine glass to her chin, sat in the library shelves of Pitou’s flat on the avenue Foch. An autumnal baby, like Suzy and me, she, too, was a Scorpio—the girl who had bridged the ten-year gap between Pitou’s detachment from his first wife and his attachment to his second.

“I was the place-holder,” she would tell me years later, “while he was waiting for you to grow up.”

They had met in September of 1964, while Terry was on assignment in Paris. He called her “Terry Bone.” A Ford model—one who Jerry Ford would later tell me was one of their most successful, during the mid Sixties she globe-hopped between her New York base and Pitou’s then apartment at 14 rue François 1er, while taking on jobs in Milan and Morocco, Portugal and Berlin.

More than a decade had passed since then. Yet, in the spring of 1977, as I scrounged through files in our library on the avenue Frédéric Le Play, clues of her were everywhere. Faded Polaroids and old postcards, love letters and telegrams.

More than a decade had passed since then. Yet, in the spring of 1977, as I scrounged through files in our library on the avenue Frédéric Le Play, clues of her were everywhere. Faded Polaroids and old postcards, love letters and telegrams.  The one I held in my hand that morning was sent by Terry in 1965, giving Pitou her flight information from Berlin. “Arriving, Air France Flight 749, Orly, November 18th”—the day of my fourteenth birthday. As I read the telegram, I imagined what I was doing at the moment he had received it: fetching books from one of a strew of lockers that lined the corridors next to the Westlake auditorium, vaguely aware of the mayhem created by classmates running excitedly through the halls–sighing deeply as I wondered when my life would begin. Who would rescue me from the tedium of my California schoolgirl existence? When would he appear?

The one I held in my hand that morning was sent by Terry in 1965, giving Pitou her flight information from Berlin. “Arriving, Air France Flight 749, Orly, November 18th”—the day of my fourteenth birthday. As I read the telegram, I imagined what I was doing at the moment he had received it: fetching books from one of a strew of lockers that lined the corridors next to the Westlake auditorium, vaguely aware of the mayhem created by classmates running excitedly through the halls–sighing deeply as I wondered when my life would begin. Who would rescue me from the tedium of my California schoolgirl existence? When would he appear?

As an adolescent, I had often spoken to my future husband. At night, alone in my bed, I would whisper to him, begging him to find me, to appear magically before me in such a way that I would know-instantly-that he was the one I was waiting for. I believe in mental telepathy. I believe in that part of quantum physics that explains that our minds are entangled through time and space and that we can sense what’s happening to loved ones thousands of miles away. I already loved Pitou at fourteen; I just hadn’t met him yet.

On that day, twelve years later, as I sat in the study overlooking the Champ de Mars reminiscing about my adolescence, I was preoccupied with the news of Menachem Begin. He had just become the Prime Minister of Israel and I was searching for his book, “The Revolt,” in Pitou’s shelves. Renowned as the manual of guerrilla warfare studied by members of the Irish Republican Army, Terry’s telegram had fallen from its pages.

On that day, twelve years later, as I sat in the study overlooking the Champ de Mars reminiscing about my adolescence, I was preoccupied with the news of Menachem Begin. He had just become the Prime Minister of Israel and I was searching for his book, “The Revolt,” in Pitou’s shelves. Renowned as the manual of guerrilla warfare studied by members of the Irish Republican Army, Terry’s telegram had fallen from its pages.  The contrast between Pitou’s mental order of preoccupation and the insouciance of his daily life back then, as he had waited for Terry to arrive from Berlin, struck me. Pitou’s mind was always racing, always engaged in thought. You could tell by the way his eyes would dart from side to side as he attempted to make sense of the absurdity of our world. His drug of choice for diminishing the pain was to surround himself with beautiful women. That, and laugh with them. I can see him, reading about the birth of Israeli terrorism while listening to Jean Sablon singing “Ces Petites Choses,” as he planned where he would take Terry that weekend in November of 1965.

The contrast between Pitou’s mental order of preoccupation and the insouciance of his daily life back then, as he had waited for Terry to arrive from Berlin, struck me. Pitou’s mind was always racing, always engaged in thought. You could tell by the way his eyes would dart from side to side as he attempted to make sense of the absurdity of our world. His drug of choice for diminishing the pain was to surround himself with beautiful women. That, and laugh with them. I can see him, reading about the birth of Israeli terrorism while listening to Jean Sablon singing “Ces Petites Choses,” as he planned where he would take Terry that weekend in November of 1965.

I was driven to our library that day after having made a comment about the Israeli “War of Independence.” Indoctrinated as a teenager into believing that Arab intransigence, in the face of peace seeking Jews, had been responsible for the political deadlock that had led to the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, I was shocked when, expressing my opinion on the subject, Pitou had laughed in my face.

“Hasbara,” he responded. “History is the propaganda of the victors.”

At twenty-two, I had never heard of the term. The Hebrew meaning of the word Hasbara is “explanation.” But in reality, it is a form of misinformation aimed, primarily, but not exclusively, at an audience in western countries. It is meant to influence the conversation in a way that positively portrays Israeli political moves and policies, including actions undertaken by Israel in the past. Its most significant contribution, however, is a negative portrayal of the Arabs and especially the Palestinians.

As a result of hasbara, I had been brainwashed into believing the “heroic moralism” propagated by the American press during Israel’s process of nation building. Jews refer to it as the concept of tohar haneshek, or the “purity of arms,” which posits that Israeli weapons remain chaste because they are employed “only in self-defense,” and not against innocent civilians.

“But, they aren’t used in self-defense,” Pitou scoffed. “And they are used against innocent civilians; innocent Palestinian civilians.”

Giving him my deer in headlights look, he had surprised me by quashing my doubts with commentary from Begin himself.

“You don’t have to take it from me,” he said. “Read what Menachem has to say about the War in ‘48; why it was waged and how it was necessary to twist the truth to gain world sympathy for the Jewish cause. The truth is, the Palestinians were dispossessed of their land exactly as the American Indians were dispossessed of theirs.”

By the time I had finished Begin’s manifesto, I was forced to conclude that Yitzhak Rabin had just been replaced by a terrorist—an extremist—Hegelian to the core who, in his own words, employed guerilla warfare as the means to the “justifiable ends of Zionism.”

I know . . . I am engaging in polemics. But, as I have written these chapters, I have asked myself several times: what is a memoir? Is it a recollection of events? Of the places we have been to and the people we have met? Or is it the compilation of moments that have formed us, that have awakened us, to the reality of our world? I think that it is both, which is why I spend so much time attempting to explain just how it was that one man opened my eyes to political milestones and helped to form my opinions about them, while walking me through a history that had been purposefully distorted to keep public opinion under control.

“Do you know who Ze’ev Jabotinsky was?” Pitou asked, knowing full well that I didn’t. “He was a delegate to the 6th Zionist Congress. Jabotinsky was a contemporary of Theodor Herzl. In the twenties, he headed the Haganah, the underground paramilitary organization that, during the British Mandate of Palestine, became the core of the Israel Defense Forces. But he is best known for his essay, The Iron Wall. Ever heard of it?”

Like most Americans, I hadn’t. Yet it is, without a doubt, one of the most influential, formative treatises of the twentieth century—one that virtually shaped the conflict in the Middle East as we know it today.

“It was written in 1923,” Pitou continued, “and originally published in Russian. In it, Jabotinsky concluded that it was pointless to talk with the Arabs, and that the establishment in Palestine of a Zionist program would have to be executed unilaterally, and—most importantly—by force. A voluntary agreement between the Jews and the Arabs of Palestine was inconceivable. The Jews have always considered it inconceivable. Jabotinsky knew what the theft of Palestine would require: ‘an iron wall of Jewish military force’ that would result in the submission of the natives through murderous, relentless, insurrection at the hands of what we know today as the IDF.”

It was often in the moments when he was engaged in the mundane, cutting a piece of baguette or eating from a pot of French yogurt, that he would expose the cover ups we refer to as history, while explaining to me the way the world really works.

“Begin is following in Ben-Gurion’s footsteps,” he continued, “who followed in Jabotinsky’s.”

But as I first learned of the reality of Middle Eastern politics, the boldness of the Jewish plan had me perplexed. In Jabotinsky’s own words, in transforming Palestine into the “Land of Israel,” a country with a Jewish majority, Zionists had long ago understood that there was not the slightest hope of ever obtaining the agreement of the Arabs. One need only look at a map of Palestinian land loss over the last seven decades to comprehend the consequences of Jabotinsky’s Iron Wall.

The irony was too in your face to ignore: the Jewish question, the Arab question. Lebensraum—history repeating itself. Here in the States, we had another phrase for the concept: “Manifest Destiny.” All of it could be symbolized with the same logo.

The irony was too in your face to ignore: the Jewish question, the Arab question. Lebensraum—history repeating itself. Here in the States, we had another phrase for the concept: “Manifest Destiny.” All of it could be symbolized with the same logo.

So, why had I been taught that the Arabs were the aggressors?

“Hasbara!” Pitou laughed once again. “Voyons, Bérénice. Your government is the monetary and military force behind a policy of theft of Arab lands every bit as brutal as John Quincy Adam’s program for “Indian removal,” and Hitler’s annexation of Eastern Europe. And you think your historians are going to tell you the truth? The truth is never given, mon chou. You have to uncover it.”

I always have had difficulty with betrayal, in all of its forms. The belief that the foundational underpinnings of a nation’s primary institutions should be trusted—its government, judicial complex, financial structure and educational system—is, probably, a naïve one. Yet the rancor that comes from its shattering inevitably leads to a singular result: blood in the streets.  Perhaps it was for this reason that, in my youth, I fought Pitou so fervently. Letting go of one’s innocence is a bit like cracking open a jammed door that has been stuck for decades. The beautiful mess that is found on the other side of it is always painful to clean up.

Perhaps it was for this reason that, in my youth, I fought Pitou so fervently. Letting go of one’s innocence is a bit like cracking open a jammed door that has been stuck for decades. The beautiful mess that is found on the other side of it is always painful to clean up.

But Pitou had little tolerance for innocence, and no interest in protecting mine. He treated the naïve the way a kitchen maid treats paper towels—with the understanding that their use is limited and, above all, disposable. And if my naïve sensibilities were ever shaken by his no bullshit analysis of political events, his only response was to laugh. Pitou never said, “I’m sorry.” He hated the phrase. He told me that, if you are going to be sorry about anything you are planning to say or do–don’t say or do it. In short, he looked at an apology as a cop-out, a ritual as absurd as

But Pitou had little tolerance for innocence, and no interest in protecting mine. He treated the naïve the way a kitchen maid treats paper towels—with the understanding that their use is limited and, above all, disposable. And if my naïve sensibilities were ever shaken by his no bullshit analysis of political events, his only response was to laugh. Pitou never said, “I’m sorry.” He hated the phrase. He told me that, if you are going to be sorry about anything you are planning to say or do–don’t say or do it. In short, he looked at an apology as a cop-out, a ritual as absurd as  Catholicism’s obsession with confessionals—conduct that allows one to keep repeating the same error, over and over again.

Catholicism’s obsession with confessionals—conduct that allows one to keep repeating the same error, over and over again.

“I’m not going to apologize to you for what is happening in the world,” he remarked. “If anything is to change, you have to admit to it, look it squarely in the face and say—yes—that is true, that happened—and it is inexcusable. Après tout, what is the difference between a Holocaust denier and an American who remains ignorant of the genocide that the Jews are perpetrating upon the Palestinians today? Do you think this policy can be excused? Because, that is what an apology is. A plea to excuse inexcusable behavior.”

It would have been easy to label him anti-Semitic. Too easy. For, as a journalist, it simply had been impossible for Pitou to ignore the unspoken side of Jewish history that, until meeting him, had escaped me completely.

“It’s the reason that a written constitution has never been adopted by Israel,” he smirked. “For it would have to be a constitution for the Jews only, to the exclusion of the Arab populace.”

The reality is that the State of Israel officially discriminates in favor of Jews and against non-Jews in so many domains of life—residency rights, the right to work and the right to equality before the law—that if this favoritism were applied in any other part of the world against the Jews, such practice would instantly and justifiably be labeled “anti-Semitism,” no doubt sparking massive public protests. What brand of irony allows us to cast a blind eye to the prejudice levied by Jewish Semites against their Palestinian Semitic brethren while failing to label the Jews as the instigators of “anti-Semitism” instead of, solely, as its victims?

The reality is that the State of Israel officially discriminates in favor of Jews and against non-Jews in so many domains of life—residency rights, the right to work and the right to equality before the law—that if this favoritism were applied in any other part of the world against the Jews, such practice would instantly and justifiably be labeled “anti-Semitism,” no doubt sparking massive public protests. What brand of irony allows us to cast a blind eye to the prejudice levied by Jewish Semites against their Palestinian Semitic brethren while failing to label the Jews as the instigators of “anti-Semitism” instead of, solely, as its victims?

Sitting at the antique writing-table in Pitou’s study as I flipped through the Terry Bone memorabilia he had inserted between the pages of “The Revolt,” I thought of comments my Third Armored Division lieutenant of a father had made to my mother shortly after the end of World War II. “The Third World War,” he told her, “will begin in the Middle East.”

It was difficult to ignore Israeli politics in 1977 in Paris. It may have been the year that Apple incorporated and Elvis would give his last performance; the year when the CIA released documents under the Freedom of Information Act revealing it had engaged in mind control experiments, the Senate conducted hearings on MKULTRA, and John Lennon was granted a green card. But it was the centuries long causes of the Arab/Israeli malaise that I found of most interest back then. As Begin continued with Jabotinsky’s Iron Wall policy, I would spend long hours listening to friends – to a side of the conflict rarely exposed, let alone admitted to, in the U.S. I took heart in the fact that President Carter was pleading for a Palestinian homeland and that he had met with Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat, at the White House; that Sadat had been the first Arab president to address the Israeli Knesset that fall and that, in December, Egyptians and Israeli representatives had gathered in Cairo for the first formal peace conference ever. But the French were skeptical, and rightfully so. They understood the meaning of “hasbara.”

Unlike the pro-Israeli stance of Americans, the French were of a decidedly pro-Arab bent. In 1974, their Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jean Sauvagnargues, had been the first Western official to meet with Yasser Arafat, in Beirut. A year later the PLO opened its first European office in Paris. And in 1977, France granted asylum to Ayatollah Khomeini.

Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was the President of the Republic at the time, having defeated Socialist candidate François Mitterrand by a mere 425,000 votes three years earlier —the closest election in French history. Giscard had promised “change in continuity,” whatever that means. In a pretentious way, it was reminiscent of “Let’s get this country moving again,” the campaign slogan used by Giscard’s idol, John F. Kennedy, in 1960. VGE emulated JFK in more ways than one. A descendant of Louis XV on his mother’s side, like Kennedy, he was a grand séducteur known for abundant infidelities with actresses and intellectuals, duchesses and the daughters of ambassadors. But the affair that I remember involved someone far closer to home: our next door neighbor, on the rue Frédéric Le Play, and heir to a dynastic fortune based upon steel mills established at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was the President of the Republic at the time, having defeated Socialist candidate François Mitterrand by a mere 425,000 votes three years earlier —the closest election in French history. Giscard had promised “change in continuity,” whatever that means. In a pretentious way, it was reminiscent of “Let’s get this country moving again,” the campaign slogan used by Giscard’s idol, John F. Kennedy, in 1960. VGE emulated JFK in more ways than one. A descendant of Louis XV on his mother’s side, like Kennedy, he was a grand séducteur known for abundant infidelities with actresses and intellectuals, duchesses and the daughters of ambassadors. But the affair that I remember involved someone far closer to home: our next door neighbor, on the rue Frédéric Le Play, and heir to a dynastic fortune based upon steel mills established at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Catherine Schneider was an intelligent blonde beauty and cousin to the French President’s wife, Anne-Aymone. In the early years of Giscard’s presidency, Schneider was also the wife of Pitou’s old friend, Roger Vadim. His fourth wife, to be exact, following in the footsteps of Brigitte Bardot, Annette Stroyberg, Catherine Deneuve, with whom Vadim lived for three years, and Jane Fonda. It was not uncommon for me to return home at night from Merrill to find Vadim in the living room conversing with Pitou. Smoking heavily, with a glass of whiskey in his hand, his years overlooking the Champ de Mars were not his best. Late in the evenings, after Vadim had returned home, Pitou would recount the bits of information gleaned, confessions that had slipped from lips loosened by the sway of Jack Daniels.

Catherine Schneider was an intelligent blonde beauty and cousin to the French President’s wife, Anne-Aymone. In the early years of Giscard’s presidency, Schneider was also the wife of Pitou’s old friend, Roger Vadim. His fourth wife, to be exact, following in the footsteps of Brigitte Bardot, Annette Stroyberg, Catherine Deneuve, with whom Vadim lived for three years, and Jane Fonda. It was not uncommon for me to return home at night from Merrill to find Vadim in the living room conversing with Pitou. Smoking heavily, with a glass of whiskey in his hand, his years overlooking the Champ de Mars were not his best. Late in the evenings, after Vadim had returned home, Pitou would recount the bits of information gleaned, confessions that had slipped from lips loosened by the sway of Jack Daniels.

“Catherine was un amour de jeunesse de Valéry,” Pitou remarked. “And she is still getting calls in the middle of the night . . . from l’Élysée.”

“Catherine was un amour de jeunesse de Valéry,” Pitou remarked. “And she is still getting calls in the middle of the night . . . from l’Élysée.”

If the press was aware of Schneider’s nocturnal visits to the palace, they weren’t reporting it.

“At least Vadim is being saved that humiliation,” Pitou added.

But Schneider had found other ways to humble her husband.

“He eats alone each night,” he continued, “served left overs by the servants in the kitchen.”

Ouch.

It might be difficult for an American, today, to understand why the image of Vadim eating alone dans la cuisine provoked such a reaction in us. But, back then, we ate most nights in a formal dinning room where we spent some of our best moments exchanging ideas with each other while our butler, Fahrid, attended to us. Over wine and under soft lighting, we laughed and argued, lamented and celebrated, deepening our relationship until it could be spelled with a capital R.  To relegate a man to table scraps each night while you’re out, doing who knows what, is conduct appropriate for your dog, not your husband.

To relegate a man to table scraps each night while you’re out, doing who knows what, is conduct appropriate for your dog, not your husband.

That February, Vadim decided to divorce Catherine Schneider.

Don’t get me wrong. I have wonderful memories of eating in the kitchens of Paris, mine and those of dear friends. But I was never alone. They were the one room in the house that, usually, had been left untouched for decades, their charm emanating–not from the stainless steel Sub-Zeros and Kitchen Aid appliances so common in the States, but from the open windows overlooking the chestnut trees that lined the streets, the cracked tile flooring that hadn’t been touched since the thirties, the red and white waxed cloths that, invariably, covered the tables in the center of the rooms, and the plates of pâté and cheeses, cornichons and viande des Grisons that adorned their surfaces.

We often dined with Alain Demachy during those years. He had been one of the first on Pitou’s endless list of copains to whom I was introduced in the early days of our relationship. His splendid apartment, on the avenue Montaigne, had served as the backdrop for evenings of abundant food accompanied by fine wines and intelligent conversation. Rarely were Pitou and Alain in agreement. Mais non, Pitou ! is a phrase I remember hearing repeatedly. Yet the intellectual discord between the two stimulated them, and they always managed to finish a tête-à-tête by laughing.

The communist and socialist parties had won in the French municipal elections that March, and with the prospect of the 1981 elections already on the lips of the French, I remember Alain suggesting, one evening, that perhaps a socialist government under Mitterrand wouldn’t be all that bad.

“Après tous,” he interposed, “les Français ont besoin d’un père.” [1]

It was a remark that astonished me. But Alain just remained calm as he listened to my contrary opinion while puffing at the cigarette in perpetuity at his lips.

“Bérénice,” he commented. “Why do you persist in believing that people want to make decisions for themselves? They don’t. They want to be told what to do. And then, they want to rely on someone else to do it for them.”

At twenty-five, I fervently disagreed with Alain. At sixty-five, I no longer do.

He was always on the edge of being cutting; he never minced his words. Forever on the prowl for money, he lived lavishly among the super rich whom he counted as his clients. I once mentioned to Alain that I loved Herbert von Karajan and would snatch up any of his performances from the Berlin Philharmonic.

Alain grimaced. He had renovated an apartment for the Austrian conductor; von Karajan had refused to pay for the work.

I had heard so many stories about the rich and famous refusing to settle their bills with their tailors. But with their interior decorator? Von Karajan’s vanity was legendary and, in the face of it, I was surprised that Alain hadn’t kept one step a head of the man with his accounting. Conceit is, after all, the sister of arrogance. Then there was von Karajan’s tyranny to consider. The despotic maestro who, in his youth, had been a Nazi, had his ticks—perhaps the strongest sign of a personality disorder. He insisted on being filmed from his left side, his “best side.” But his self-admiration didn’t stop with his self. His principal flute, James Galway, was never visible in his films; it seems that the conductor had an aversion to Galway’s facial hair. Nor did he like baldness, a fact that resulted in many of his musicians wearing wigs for their performances. At von Karajan’s beck and call around the clock when he was in Berlin, convened at a moment’s notice for rehearsal, he commanded complete authority over his orchestral players. Magnetism? Charisma? Whatever the reasons, Alain had ignored the warning signs, and had paid dearly for it.

“He believes that he’s a gift to the world,” Alain commented. “So, why should he pay?”

“Detestable” he added.

Where money is concerned, Alain never joked. A perfectionist to a fault, his work demanded too much of the medium of exchange to take it lightly. But it kept him in a perpetually nervous state. And yet, the beauty Alain left in his wake, as he labored at restoring proportion, transforming space and generally turning the mundane into the exceptional, excused the sudden outbursts of temper and castigating criticisms of those who could not appreciate the skill involved in his profession—those unfortunate many who pass through life without a trained eye. He had no patience for people without taste. Still, he had his soft spots.

They were usually for women, for their trials and tribulations with which, oddly, he was able to empathize. Alain’s most important client was Edmond de Rothschild, for whom he magnificently restored and remodeled properties throughout Europe—his chalet in Megève, apartment in Paris, and chateau in the southern part of the Médoc, to name a few. And so, it wasn’t surprising that, over the years, he had become quite close to Edmond’s wife, Nadine. I never much cared for the woman. A film starlet who had resorted to more than a few cheese shots to gain recognition, she struck me as falsely imperial—inflicted by the pretention that only the ascent from nothingness to mega wealth can create. But then, observing people is like witnessing an accident. What you see depends upon where you are standing. I stood at a distant edge, our circles overlapping sporadically, from time to time.

She once told me that, upon her marriage to Edmond in 1963, he “only” gave her a million dollars—pocket change, to be sure, for a Rothschild who was once rumored to be the richest man in the world. Still, the sum is easily the equivalent of twenty million dollars today. In my presence, she gave the impression of being wary. But then, I imagine she was wary of all young females. Edmond had a charming disposition and a roving eye to match, which, in his later years, led him to produce at least one illegitimate child. The mistresses of Europe’s male power brokers intrigued me. Seeing them, hearing of them, was like experiencing a parallel universe. There was an on/off switch they installed in their benefactors, capable of obliterating one plane of existence so as to enter another. And these women knew how to flog it–expertly. You could dine with a man and his wife on one evening, run into him on the street the next day in the presence of his grande horizontale, and find yourself wondering if the prior night had been nothing more than a dream. But, contrary to the myths perpetuated about the accepting nature of European wives, the ones whom I frequented were anything but complacent. Nadine never mentioned the “other women.” But Alain knew they bothered her. When Edmond made the mistake of inviting him to a small dinner party in honor of his latest lady of the night, in spite of Rothschild’s enormous wealth and power, and the decades of friendship between the two men, Alain politely refused.

“Nadine would have seen it as a betrayal,” he told me. “I couldn’t hurt her like that. C’était louche d’Edmond de m’inviter.”[2]

His apartment was a study in formal, yet comfortable, elegance. When you dined at Alain’s, you didn’t do so in chairs. You fell backwards into plush sofa cushions made of one hundred percent goose down. You drank from Baccarat crystal while scraping the surface of Minton china plates with heavy eighteenth century silverware. The lighting was just golden enough to flatter the aging faces of his middle-aged female guests while illuminating the beauty of the young women he loved to surround himself with.

His apartment was a study in formal, yet comfortable, elegance. When you dined at Alain’s, you didn’t do so in chairs. You fell backwards into plush sofa cushions made of one hundred percent goose down. You drank from Baccarat crystal while scraping the surface of Minton china plates with heavy eighteenth century silverware. The lighting was just golden enough to flatter the aging faces of his middle-aged female guests while illuminating the beauty of the young women he loved to surround himself with.  Rare sixteenth century mirrors adorned the walls, their glass surface reflecting a depth one felt one could dive into. More often than not, a fire burned in the living room hearth—waiting to warm you along with the Armagnac specially chosen for the evening. And yet, amidst this backdrop of rafinement and carefully calculated décor, there were no rules. A laissez-faire mentality reigned chez Alain, where the young and the broke, sporting jeans and turtleneck sweaters, effortlessly mingled with the old and the rich, clad in dinner jackets and floor length evening gowns.

Rare sixteenth century mirrors adorned the walls, their glass surface reflecting a depth one felt one could dive into. More often than not, a fire burned in the living room hearth—waiting to warm you along with the Armagnac specially chosen for the evening. And yet, amidst this backdrop of rafinement and carefully calculated décor, there were no rules. A laissez-faire mentality reigned chez Alain, where the young and the broke, sporting jeans and turtleneck sweaters, effortlessly mingled with the old and the rich, clad in dinner jackets and floor length evening gowns.

On weekends, Pitou and I would often visit with him at his manoir at Detilly in the heart of the Loire Valley. In fact, we had been with him, vacationing, when he had found the rambling estate in such a dilapidated condition that the chickens were living inside the house  with the caretaker of forty years. We watched, as he painstakingly renovated the structure—replacing the roof, restoring blocked chimneys, resurfacing stone floors, and adding six bathrooms. He broke through walls to revive the original architecture, and then lined the living room with heavy sisal—an unexpected touch that so enchanted me, I asked him to replicate the effect in our apartment on the Champ de Mars. The kitchen counters were made of cork, and it’s fireplace, always lit in the winter, in combination with Alain’s love of food, transformed the room into the central living area, as he attended to every minute detail of refurbishing the property. My best memories of Europe are of the simple moments spent with friends in warm winter kitchens, with a bottle of good wine and baguette smothered with rillettes.

with the caretaker of forty years. We watched, as he painstakingly renovated the structure—replacing the roof, restoring blocked chimneys, resurfacing stone floors, and adding six bathrooms. He broke through walls to revive the original architecture, and then lined the living room with heavy sisal—an unexpected touch that so enchanted me, I asked him to replicate the effect in our apartment on the Champ de Mars. The kitchen counters were made of cork, and it’s fireplace, always lit in the winter, in combination with Alain’s love of food, transformed the room into the central living area, as he attended to every minute detail of refurbishing the property. My best memories of Europe are of the simple moments spent with friends in warm winter kitchens, with a bottle of good wine and baguette smothered with rillettes.

But with the birth of our daughter, our focus had changed from weekends in the country, with the fashionable and the noted, to the playpen in our bedroom and the pram in the entrance hall. I was still working at Merrill but finding it increasingly difficult to do so. Pitou was spending more time with Devon than I could, often attending to her in the early evening when, due to the time difference between Paris and New York, I was still at the office trading. By the time I got home each night, he had already fed and bathed her, and put her down to bed. I’d creep into her room just in time to see her dozing off, her fat little cheeks framed by blonde curls, with tiny beads of sweat on her upper lip from the effort expended on a baby bottle she had let fall to her side as the sleep had overcome her. I wondered if she had wondered where I had been all day, and vowed to make up for the lost moments over the weekend. But babies are voracious consumers of a mother’s affection, and I never seemed to have enough to give.

Before she had celebrated her first birthday, she let me know that I was no longer her favorite. She resented the hours I spent away, seemingly demanding that I make the supreme sacrifice as a mother by consecrating all of my attention on her. And when I didn’t, she communicated her disfavor with an aloof and jarring stare that told me she would not easily forgive. When in the arms of her father, should I dare to approach, I was swiftly met with her rebuke.

“NO,” she would scream, as she placed her little hand on my chest to push me away.

For all the talk of women’s progress in the work place during the twentieth century, little is mentioned of the cost. Feminism had trained me to reject the model of the stay-at-home mom as an old-fashioned, oppressive stereotype even though, more and more, it was appearing to me as simply a natural instinct. It made me wonder if the filmmaker and one-time candidate for governor of Nevada, Aaron Russo, had told the truth when he revealed the substance of conversations with his once friend, Nick Rockefeller.

According to Nick, the Rockefeller Foundation had created and bankrolled the women’s liberation movement—with sinister goals in mind.

“We did it to destroy the family,” he told Russo, while explaining that population reduction was the fundamental aim of the global élite and what better way to achieve it than by destroying the family unit?

Russo had been invited by Rockefeller to join the Council on Foreign Relations but had rejected the invitation by stating that he had no interest in “enslaving the people.”

“Why do you care about the serfs?” Rockefeller coldly questioned. “You’re an idiot.”

Stumped by Nick’s reaction, Russo asked him what possible reason the Rockefellers could have for wanting to destroy the family?

There were two reasons, Nick replied.

“We couldn’t tax half the population before Women’s Lib.”

Whatever you may think of feminism, it is undeniable that, in one fell swoop, the movement had doubled the government’s tax base while dramatically cutting the corporate wage base.

Even Gloria Steinem has admitted that the CIA, peopled by blue bloods from the New York banking establishment and graduates of Yale University´s secret “Skull and Bones” society, funded Ms Magazine–with the stated goal of breaking up families and taxing women. And yet, our main misconception about the CIA is that it serves US interests when, in reality, it has always been the instrument of a dynastic international banking and oil élite: the Rothschilds, the Rockefellers, the Morgans, etc., structured by the Royal Institute for Internal Affairs in London and its US branch, the Council for Foreign Relations, in New York.

Even Gloria Steinem has admitted that the CIA, peopled by blue bloods from the New York banking establishment and graduates of Yale University´s secret “Skull and Bones” society, funded Ms Magazine–with the stated goal of breaking up families and taxing women. And yet, our main misconception about the CIA is that it serves US interests when, in reality, it has always been the instrument of a dynastic international banking and oil élite: the Rothschilds, the Rockefellers, the Morgans, etc., structured by the Royal Institute for Internal Affairs in London and its US branch, the Council for Foreign Relations, in New York.

But there was a more ominous reason behind the movement.

“Now we get your kids in school at an early age,” Rockefeller continued, “where we can indoctrinate them on how to think so that it breaks up the family. Your kids start looking to the State as the family, to the school as their family, and not to their parents.”

Was it a coincidence that Pitou and I had chosen to live on the avenue Frédéric Le Play—a street named after the nineteenth century French sociologist and economist who had placed the family unit at the center of his social and political vision? Le Play argued that the family is the center of social authority, the most basic unit of economic life, and believed fervently in la femme au foyer—so much so that he calculated her value, unsentimentally, in terms of her unwaged work of child rearing and education, house keeping and tending to the garden or livestock, as a measurable economic contribution on a par with that of her wage earning husband.

When I first listened to a Russo interview where, courageously and with a wry sense of humor, he had attempted to warn the American public of the war being waged against the family unit—a war which, instead of using the traditional method of dividing in order to control by pitting Republicans against Democrats or conservatives against liberals, now set women against men—I thought back to the propaganda that was used against my generation when we were young women. Whom of us can forget the mind numbing stupidity of the “You’ve come a long way, baby” ads? In my senior year at Westlake, the Phillip Morris Company had launched the memorable campaign to sell Virginia Slims. But, for anyone familiar with the philosophy of social control propagated by Edward Bernays, it was selling much more than just cigarettes.

The imagery of enslaved women, stuck in their homes tending to the kitchen and their children, juxtaposed against a photo of a young liberated woman with a Virginia Slim in hand, harkened back to Bernay’s campaign of “Freedom Torches” during the twenties. One of Bernays’ early publicity campaigns, it is the stuff of legend. Staging a demonstration at the 1929 Easter parade, he hired fashionable young women to flaunt their torches of freedom in public despite the social taboos against women smoking. Using cigarettes as symbols of emancipation and equality with men, he used the phrase to encourage women to smoke by exploiting their aspirations for a better life. Similarly, he promoted Lucky Strikes by convincing women that the forest green hue of the cigarette pack was a “ fashionable color” and that smoking them made women “lucky in love.” At home, however, Edward was engaged in an entirely different pursuit—that of persuading his wife to kick the nasty habit. Finding the pernicious packs of her Parliaments throughout the house, and aware of the early studies linking smoking to cancer, he snapped her cigarettes in

The imagery of enslaved women, stuck in their homes tending to the kitchen and their children, juxtaposed against a photo of a young liberated woman with a Virginia Slim in hand, harkened back to Bernay’s campaign of “Freedom Torches” during the twenties. One of Bernays’ early publicity campaigns, it is the stuff of legend. Staging a demonstration at the 1929 Easter parade, he hired fashionable young women to flaunt their torches of freedom in public despite the social taboos against women smoking. Using cigarettes as symbols of emancipation and equality with men, he used the phrase to encourage women to smoke by exploiting their aspirations for a better life. Similarly, he promoted Lucky Strikes by convincing women that the forest green hue of the cigarette pack was a “ fashionable color” and that smoking them made women “lucky in love.” At home, however, Edward was engaged in an entirely different pursuit—that of persuading his wife to kick the nasty habit. Finding the pernicious packs of her Parliaments throughout the house, and aware of the early studies linking smoking to cancer, he snapped her cigarettes in  half before throwing them in the toilet.

half before throwing them in the toilet.

Russo was simply arguing that similar forms of deception now were being used to, unwittingly, herd the population, like the cattle that the élite see them for, into the abattoir.

For anyone who might be in doubt, I am not advocating that we return to the days when newspapers published ads for jobs on different pages, segregated by gender. Or employers legally paid women less than men for the same work. Or bars refused to serve women unaccompanied by a man. Or states excluded women from jury duty. Much like God, evolution works in mysterious ways, and however sinister the motives of these “manufacturers of consent” who operate behind the scenes, I do believe their campaigns will, eventually, backfire in their faces. But, for that to happen, we need to follow the advice of the former chairman and CEO of IBM, Thomas Watson.

We need to “Think.”

Bernays, of course, was of the firm belief that we never would. His mother, Anna, was Sigmund Freud’s sister–a fact that he always managed to mention. And his father, Ely Bernays, was the brother of Freud’s wife, Martha.

By drawing on the insights of his uncle, he developed an approach he dubbed “the engineering of consent.” In the process, by appealing—not to the rational part of the mind, but to the unconscious—he provided our leaders with the means to “control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing about it.”

Is it no wonder that he is considered “the father of public relations”? His seminal work, “Propaganda” was published in 1928. In it, he argued that public relations is “a necessity.”

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society,” Bernays stated. “Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, and our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of…. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind.”

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society,” Bernays stated. “Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, and our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of…. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind.”

Ironically, even though Bernays saw the immense power of propaganda, he failed to imagine that his writings could become a tool of men who would just as soon see him and his kind dead: the Third Reich. In the 1920s, Joseph Goebbels became an avid admirer of Bernays and his writings – despite the fact that Bernays was a Jew.  When Goebbels became the Nazi minister of propaganda, he exploited Bernays’ ideas to the fullest by creating a “Fuhrer cult” around Adolph Hitler.

When Goebbels became the Nazi minister of propaganda, he exploited Bernays’ ideas to the fullest by creating a “Fuhrer cult” around Adolph Hitler.

Clearly, history has proven that, unless we are willing to “think,” the means for shaping our opinions will be successfully employed for any purpose whatsoever, whether beneficial to human beings or not. Which is perhaps why Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter warned President Franklin Roosevelt against allowing Bernays to play a leadership role in World War II. Describing him and his colleagues as “professional poisoners of the public mind, exploiters of foolishness, fanaticism, and self-interest,” the justice was well ahead of his time; for he understood that these “Mad Men” are just that—mad.

No doubt, in making these statements, some will label me a “conspiracy theorist”—that catch all phrase glibly used to attack those who dare challenge the Official Narrative, an étiquette that anyone can resort to when he wants to, effortlessly and without thought, relegate a contrary opinion to the dustbin of debate. No other allegation can, instantly, transform an individual, who thinkingly questions the Established Order, into a verified “paranoid” nut.

Interestingly, the term was first coined by the CIA, which drummed it up in a 1967 dispatch as part of its psychological warfare operations when it found itself having to combat all sorts of “conspiracy theorists” unwilling to accept the Warren Report at its word. The dispatch, which recommended methods for discrediting such “nuts” was marked “psych” – short for “psychological operations” or disinformation – and “CS” for the CIA’s “Clandestine Services” unit. It was produced in 1976 in response to a Freedom of Information Act request by no other than the New York Times. So, if you are ever tempted to use this meaningless label again, know that it was devised with a troubling aim in mind: to discredit “conspiracy theorists” so as to INHIBIT the circulation of thoughts that bring the Shadow Government’s agenda into question.

There is only one other tactic of debate more indicative of a feeble mind: ad hominem.

Pulling the goose down comforter over Devon that I had made for her while pregnant, the reality was slowly dawning upon me that I didn’t want to see her in day care. I didn’t want somebody else forming that blank slate of hers that would one day become her mind. I had come a long way. I had learned to recognize hasbara in all of its forms.

Already, I was resolving to leave Merrill Lynch.

[1] “After all . . . the French need a father.”

[2] “It was despicable of Edmond to invite me.”

much too political with a skewed interpretation of Arab-Israeli relations. Israel is obviously forced to do what she is doing in light of continued Arab perfidy and misrepresentation. each time she extends an olive branch she must do so with a mailed glove, and be careful at that.

you may think that your position is chic, but it is naive, pretentious and unproductive.

otherwise, your text is interesting.

LikeLike

why “moderate” all comments? is not a blue sky forum most honest and productive?

LikeLike

Allen, thank you for your comments. First, WordPress sets the agenda as far as allowing the author to moderate the comment section. In any event, know that, to date, I have never disallowed a comment. I welcome contrary opinion. It’s my nature. Second, if you have read Begin’s book, “The Revolt,” and Avi Shlaim’s take on “The Iron Wall,” then you will know that my position is far from “naive.” That said, I have included a link to Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s complete original transcript of The Iron Wall, which was originally published in Russian, and would encourage everyone, at the very least, to read it before commenting about “Arab perfidy.” Trust that I find nothing “chic” about the genocide that has been wrought upon the Palestinian population by the IDF. And, while I recognize that my position is “unproductive” for IT’S ultimate goals, I take exception with your comment that the writing is “pretentious.” The word literally means “attempting to impress by affecting greater importance than is actually possessed.” What could be more important than exposing ALL SIDES to an issue that could create a Third World War?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely fascinating, the way you write is like looking at a beautiful tapestry incorporating important and relevant references to the time and beyound, none more than to this present day. You have led an incredible life Berenice, and as a reader you feel lucky that somebody can impart their knowledge in such an eloquent and entertaining way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dorthe, Thank you so much for your lovely commentary. In it, you have caught the essence of exactly what I am trying to achieve.

LikeLike

You are welcome Berenice, and may I just add the way you can recall ad verbum sentences in discussions that took place years ago is testimony to the life you lived and loved in France and the knowledge you absorbed from Pitou and his friends. By no means do I wish to imply you are not capable of forming your own opinions about things–au contraire, and that is what is so compelling about this book.

LikeLike

Anytime you put your head above the parapet strong opinion will follow but your writing is excellent and transports the reader back to a younger more innocent world so please continue and take all comment be it compliment or criticism as an accolade evidencing the difference you make and the time travel you facilitate ❤❤❤

LikeLike

Anytime you put your head above the parapet strong opinion will follow but your writing is excellent and transports the reader back to a younger more innocent world so please continue and take all comment be it compliment or criticism as an accolade evidencing the difference you make and the time travel you facilitate ❤❤❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your primary source “fly-on-the-wall” observations of, & high sensitivity to, aspects of 70’s Parisian society are enlightening in a way academic history texts never manage. “Tout la Paris,” in a country smaller than California & peopled by a tightly-knit web of extraordinary characters you so succinctly describe, created an outsized positive symbiosis that has contributed much to what we call civilization–architecture & design, literature, art & insights into a quality of balanced existence that has enriched our lives. Your memoir of a place & time gone forever offers us opportunity to consider what it means to live well while positively growing our own communities, where ever they may be.Thank you Berenice, for this new chapter of your loving blog–appreciated in part because it’s so different than my own life in the wilds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. What a tribute. You’ve put a smile on my face. Thank you, for your well written, thoughtful commentary.

LikeLike

I love your writing, Berenice. I always have and always will. But I wish you wouldn’t get political. Yes, it was part of your relationship with Pitou but there are so many other interesting stories to tell about the places you’ve been and people you’ve met.

Even though Pitou has been gone five years, not much has changed with the Arab/Israeli conflict. There will never be peace so long as Israel exists. Whether a one-state or a two-state solution is possible, it doesn’t matter…nothing will work until Israel and its Jewish population are annihilated.

And where would Pitou have the Jews go? It was post-WWII. Millions have been killed off by Hitler. The can’t go back to Germany.. They can’t go back to Poland or Austria and even Russia. Even the US (FDR) turned away a ship filled with Jews only to have them return to Europe and sent to their deaths. They needed a homeland where they could live free and feel a little safe. Great Britain drew the boundary lines and the Israelis settled there. It was the land of their forefathers, the land of their sacred Western Wall. They worked the land, created acquifers, built houses, grew food. All the while, the Arab-Palestinians were plotting to take the land the Israelis had been given. Arab leaders told their people to leave, get out, we’ll wage war and win against the Israelis. Then you can go back and claim for yourselves the land and everything the Jews built.

Guess what? The Israelis prevailed against the Arabs. The Arabs have waged several more wars, with the Israelis winning almost every time. The lines of their state have grown to include territory they won. “To the victor goes the spoils.”

Instead of working to build their cities and infrastructure, what do the Palestinians do? They lob rockets into Israel, they blow up busses, they indiscriminately kill Israelis no matter if it’s a man, woman or child. They build tunnels and kidnap Israelis. They teach children that Jews are lower than dogs and pigs. They teach children to become suicide bombers. Did Pitou foresee this kind of behavior? Would he still have the Jews give back the land that they’ve worked so hard to make fruitful?

I think that’s enough from me on this topic. I don’t want to start a firestorm of controversy. I hope everyone has enjoyed each and every installment of “Pitou, My Love” as much as I have. I always look forward to your next story. What a fascinating life you had with Pierre. I hope you will publish the complete story in book form. Then I can sit by the fire with a cup of tea and dive in again. Love you.

LikeLike

Adie, I understand your passion. You sound very much like I did, many years ago. Please know that while I empathize with the suffering of the Jews, particularly at the time of the Second World War, the plans I speak of in this post to dispossess the Palestinians of their land, as evidenced by the map I have included, predates World War II by more than 20 years. As I mentioned in another reply, I have included a link to the entire original text of Jabotinsky’s Iron Wall at the photo of Avi Shlaim’s book on the subject. Please also note that EVERY HISTORIAN I have cited on this subject is Jewish, all of whom speak of the conduct of the IDF over the past 70 years with utter abhorrence (perhaps the greatest indication that we have been lied to by the mainstream media). Also, please understand that I have not made any statements lightly, simply based upon Pitou’s opinions, or without conducting my own research. Finally, while I have no solution to the problem, my hope is that more Americans will, also, research the history of the Arab Israeli conflict. It is a difficult thing to do. In addition to the books I have cited in this post, before forming an opinion, I would ask that you, and anyone else interested in uncovering a well rounded truth of the history of these warring peoples, read the following Jewish authors on the subject:

Taking Sides: America’s Secret Relations With Militant Israel

By Stephen J. Green

Jewish History, Jewish Religion: The Weight of Three Thousand Years

By Israel Shahak

Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel

By Israel Shahak

Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians

By Noam Chomsky

LikeLike

As always, so entertaining! I remember well the days of Terry Reno … I looked at her too in the magazines and who knew that the karma would dictate that your paths were being influenced by the same energy, albeit ever so distant? The history — I can appreciate. I was naive also until I met a man who flew alongside Ezer Weizman, Lou Lenart (Israeli 1948 War Hero) and he educated me in Israeli politics…though not to the degree that Pitou taught you. Imagine if Pitou were here today, what his opinion would be of the agenda now!

You’ve been blessed with the experiences you are sharing with us and in this, you are keeping alive the legacy of all that you were given and we can, vicariously, experience with you! Keep going! It’s delicious!

LikeLiked by 1 person