SENECA SAID THAT THE LESS WE DESERVE GOOD FORTUNE the more we hope for it. Nonetheless, I have never lost sight of the importance of being thankful for it; for my luck that, despite the challenges of life, has always followed me wherever I have travelled. The park in Paris that I called home is one of the most sought after spots in the city. There, only the sound of birds chirping and children playing disturbs your peace. There, the city smog evaporates through the verdant foliage of the horse-chestnut and linden trees. A day wouldn’t pass without me standing at my windows in silent meditation, awe-struck by the beauty with which I was blessed. But never more so than as the end of my séjour in

SENECA SAID THAT THE LESS WE DESERVE GOOD FORTUNE the more we hope for it. Nonetheless, I have never lost sight of the importance of being thankful for it; for my luck that, despite the challenges of life, has always followed me wherever I have travelled. The park in Paris that I called home is one of the most sought after spots in the city. There, only the sound of birds chirping and children playing disturbs your peace. There, the city smog evaporates through the verdant foliage of the horse-chestnut and linden trees. A day wouldn’t pass without me standing at my windows in silent meditation, awe-struck by the beauty with which I was blessed. But never more so than as the end of my séjour in  Paris approached.

Paris approached.

Originally farmland, it had once served as grounds for training maneuvers for l’École Militaire, the academic college for officers that Louis XV founded. Napoleon had been a cadet there. And I thought it fitting that Catherine Hennessy lived in the apartment above us. Richard Hennessy, the founder of the cognac dynasty she had inherited, had lived the military life, fighting Protestants in Louis XV’s Irish Brigade.

One afternoon in mid September of 1978, her husband, Eric de Lavandeyra, had just finished having lunch with us when, still seated at our table, the agent de change pour la bourse Parisienne commented on the dining room’s familiar architecture.

“A mason once lived here,” he said.

“Tiens,” Pitou remarked, while sipping on a Napoleon cognac Eric had brought for us. “How do you know ?”

“Look at the wood paneling that’s been added to the room,” Eric answered. “It was done to recreate the proportions of the temple. And the pillars at the entrance. They’re not there for support. In Freemasonry, they represent one of the Brotherhood’s most recognizable emblems. They’ve been placed there to symbolize Boaz and Jachin.”

“Look at the wood paneling that’s been added to the room,” Eric answered. “It was done to recreate the proportions of the temple. And the pillars at the entrance. They’re not there for support. In Freemasonry, they represent one of the Brotherhood’s most recognizable emblems. They’ve been placed there to symbolize Boaz and Jachin.”

According to the Bible, Boaz and Jachin were the two pillars that stood at the entrance of Solomon’s Temple. The Jachin pillar characterized King Solomon, while the Boaz pillar represented King David. This said, it would be a mistake to believe that the symbolism behind these pillars  originate in Jewish tradition. Since the dawn of civilization, twin columns have been said to guard the entrance of sacred and mysterious places—the archetypal ciphers representing an important gateway or passage to the unknown. In ancient Greece, they stood at the gateway to the sphere of the enlightened. They are The Pillars of Hercules, beyond which Plato tells us the lost realm of Atlantis was situated –a realm where the muck of the material world was left behind in order to reach a higher dimension of illumination. They are the lunar and solar channels–the Ida and Pingala that yogis teach us flow down each side of our spinal cord. Through them, when awakened by our kundalini energy coiled at their base since birth, the Eye of Horus is opened as this “Spirit Fire” lifts up through the thirty-three degrees of the spinal column to enter the human skull.

originate in Jewish tradition. Since the dawn of civilization, twin columns have been said to guard the entrance of sacred and mysterious places—the archetypal ciphers representing an important gateway or passage to the unknown. In ancient Greece, they stood at the gateway to the sphere of the enlightened. They are The Pillars of Hercules, beyond which Plato tells us the lost realm of Atlantis was situated –a realm where the muck of the material world was left behind in order to reach a higher dimension of illumination. They are the lunar and solar channels–the Ida and Pingala that yogis teach us flow down each side of our spinal cord. Through them, when awakened by our kundalini energy coiled at their base since birth, the Eye of Horus is opened as this “Spirit Fire” lifts up through the thirty-three degrees of the spinal column to enter the human skull.

It was four in the afternoon, my moment of daily respite when Devon took her nap. After Eric left, I perched myself upon the balcony off the living room overlooking the park. There, I thought back to the first time I traversed it. Seven years earlier, almost to the day, I had been alone—abandoned by Debbie who had left me to fend for myself in the city on one of the weekends when she had opted for an impromptu jaunt back to Princeton and her boyfriend, Ruffy.

I had not yet met Pitou, and the lack of him had me wondering if I had made a mistake in coming to Europe. Strolling through the walkways of the Champ de Mars had offered solace. I could easily lose an entire day there. Doing so had become my preferred way of dealing with solitude.

At its center, the avenue Joseph Bouvard cuts through the park as it encircles a large basin of water. As I thought back on those first days in Paris, the whisper of a kiss—a transformational caress—echoed, as if the Eiffel Tower, overshadowing me, served as an antenna linking me to the outer limits of space along an energetic highway of wisdom and light.

At its center, the avenue Joseph Bouvard cuts through the park as it encircles a large basin of water. As I thought back on those first days in Paris, the whisper of a kiss—a transformational caress—echoed, as if the Eiffel Tower, overshadowing me, served as an antenna linking me to the outer limits of space along an energetic highway of wisdom and light.

Umberto.

I had sensed him before I saw him. Walking along the basin’s edge toward the avenue Charles Floquet, I could hear the soft hum from the motor of his car as it crept slowly behind me to the rhythm of my steps. Top down, in a  convertible Triumph Spitfire identical to the one I drove as a teenage girl while at Westlake, he travelled at no more than five miles per hour. With his head facing straight a head, the corner of his eyes were glued to me. There was a playful smirk across his face. Engaged in a game that he knew would finish by making me laugh, he waited for a glance of recognition, thrown over my left shoulder, as I continued to walk.

convertible Triumph Spitfire identical to the one I drove as a teenage girl while at Westlake, he travelled at no more than five miles per hour. With his head facing straight a head, the corner of his eyes were glued to me. There was a playful smirk across his face. Engaged in a game that he knew would finish by making me laugh, he waited for a glance of recognition, thrown over my left shoulder, as I continued to walk.

It was late in the afternoon, the moment of the day when my most pressing concern centered upon which café I would visit for a good cup of Earl Grey. The sipping of the hot liquid, infused with the essence of bergamot, had become an afternoon ritual that, to this day, I still respect. Carette’s wasn’t far and, just as I was thinking of veering off the parkway in the direction of the Place du Trocadero, he broke the ice.

“Shall we have tea?” he asked.

His telepathic skill stopped me in my tracks.

“How did you know?” I exclaimed, finally turning to take a good look at him. “How did you know that is what I was thinking?”

Glancing at his watch, he smiled. “It’s four o’clock.”

As a child, my mother consistently warned me of the dangers of speaking to strange men. And yet, this man did not frighten me. To the contrary, in his presence I immediately felt as if greeted by an old friend; inexplicably safe. And although I had never before, nor after that day in September of 1971, accepted an invitation from an inconnue, when Umberto leaned over to open the door of his Triumph Spitfire, I fearlessly got into the car.

I only remember fragments of what happened next. I have no recollection of where we went. I do remember that he asked many questions, wanting to know everything about my life up until that point—and always with a grin, as if for some mysterious reason, he found me exceedingly amusing.

He told me that he’d been living in Rome and although possessed of a definite Italian air, his speech was free of any accent. About five-foot-ten, trim, with a matte complexion, he reminded me of a young Manley Palmer Hall—the thirty-third degree Freemason, astrologer and mystic best known for his 1928 work, The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Both his English and his French were impeccable and I would have gladly spent the entire evening with him. But, shortly after we met, he drove me back to my apartment on the rue de Lubeck. An old-fashioned gentleman, he jumped out of the car in order to open the door for me before asking for my phone number.

“Do you have something to write with?” I said.

“I’ll remember it,” he smiled.

Weeks passed before he called and, by the time he did, I had met the love of my life.

“Have you ever been to Senlis?” he queried.

Sure that I had not but before I could answer, he spoke of the medieval town and the cathedral for which it is known. About an hour north of Paris, he wanted to go there that instant, and insisted that I come with him.

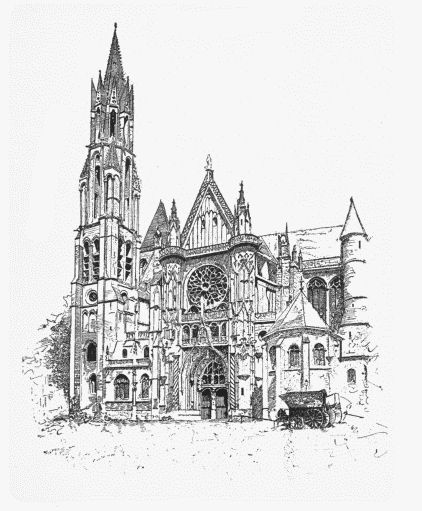

It was a grey October day, and we drove in the rain to the village that marked the Gallo-Roman remains of ancient Augustomagus. I didn’t know it at the time but, in accordance with the Hermetic principle “as above, so below,” Notre Dame de Senlis is one of eight Gothic cathedrals located in cities which correspond, in their latitude and longitude, to the visible stars of the Constellation Virgo. You may not think this fact noteworthy, today, in an age of satellite imagery. But, considering that these sacred sites were all built in the twelfth century, using the Virgo Constellation as a template for a Gothic building spree of cosmic dimensions is truly astounding. Who was behind such a plan? And why?

It was a grey October day, and we drove in the rain to the village that marked the Gallo-Roman remains of ancient Augustomagus. I didn’t know it at the time but, in accordance with the Hermetic principle “as above, so below,” Notre Dame de Senlis is one of eight Gothic cathedrals located in cities which correspond, in their latitude and longitude, to the visible stars of the Constellation Virgo. You may not think this fact noteworthy, today, in an age of satellite imagery. But, considering that these sacred sites were all built in the twelfth century, using the Virgo Constellation as a template for a Gothic building spree of cosmic dimensions is truly astounding. Who was behind such a plan? And why?

The Constellation of Virgo has long been associated with almost every major female deity in any of various worldwide early civilizations including, to name only a few: the Sumerians, who knew her as Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth; the Akkadians and Babylonians, who called her Ishtar, the “leading one” or “chief”; the Egyptians who referred  to her as Isis, the Goddess of Fertility; and the Greeks who named her Demeter, or Persephone—the Earth Goddess. The Cathedral at Senlis, along with her seven sisters via their stone steeples and special focus on a sacred network of ley lines, act as antennae for the cosmos—amplifying the energies of consciousness, the earth, and the universe.

to her as Isis, the Goddess of Fertility; and the Greeks who named her Demeter, or Persephone—the Earth Goddess. The Cathedral at Senlis, along with her seven sisters via their stone steeples and special focus on a sacred network of ley lines, act as antennae for the cosmos—amplifying the energies of consciousness, the earth, and the universe.

There are those who can see these telluric currents —vertical rays above steeples and domes, cosmic inflows that form umbrella like grids in the sky. They are as visible to some as spirit forms are to a clairvoyant, seemingly confirming—at least to a lucky few—that consciousness is a tangible form of energy. That last statement may sound grandiose. Yet, generation upon generation has recognized the geomagnetic power of these sites, with the result that each dominant culture has built their religious structures on the same spots within this sacred network as if doing so, somehow, fuels a state of shared consciousness for humanity. The Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, for example, is constructed over a temple to Diana that, in turn, was built over a stone pillar worshipped by the Gauls. And the Cathedral at Chartres, located on a ley line linking Glastonbury, Stonehenge, and the Pyramids of Egypt, is a site believed, by the Druids—the Celtic priests of Britain and Gaul—to be where the spiritual energy of the Divine Feminine emanates from underground. Serving as hubs of cosmic and earthly energy where ley lines intersect the world over, these junctures have been systematically marked with megaliths and temples, obelisks and towers—always reaching upward, toward the heavens.

And nowhere more than in Paris.

I was living on one of these energetic ley lines; it cut a swath right down the meridian of the Champ de Mars. Starting at the obelisk at the Place de Fontenoy, it darts northeast to l’École Militaire before running through the elliptical and diamond-shaped garden mandala of the Champ de Mars where I had met Umberto. From there, it continues to the Eiffel Tower—a steel spire said to attract the mysterious energy of the stars—before traveling along the Pont d’Iena, through the Place du Trocadero and toward La Défense where, finally, it culminates.

As Umberto’s Spitfire came to a halt, the downpour we experienced all morning suddenly intensified. I glanced up at the Gothic façade of the Masonic cathedral with its prominently placed twin pillars flanking its west portal. The grandeur of the structure is out of sorts with the modesty of the Medieval village. But, when it was built in the 12th century, Senlis was considered a royal city of the same rank as Paris.

As Umberto’s Spitfire came to a halt, the downpour we experienced all morning suddenly intensified. I glanced up at the Gothic façade of the Masonic cathedral with its prominently placed twin pillars flanking its west portal. The grandeur of the structure is out of sorts with the modesty of the Medieval village. But, when it was built in the 12th century, Senlis was considered a royal city of the same rank as Paris.

“I have to go inside,” he said. “I’ll just be a minute. Wait here for me.”

I couldn’t imagine this man praying inside of the cathedral. Yet it was clear that he needed to be alone. But then, why was he so insistent that I come with him on this pilgrimage?

I couldn’t imagine this man praying inside of the cathedral. Yet it was clear that he needed to be alone. But then, why was he so insistent that I come with him on this pilgrimage?

About ten minutes later he got back into the car and, grabbing the back of my neck, pulled me toward his chest. Staring intensely into my eyes, he paused for a few seconds before kissing me.

I have been kissed with affection, kissed with longing, kissed with deep passion and kissed with profound sadness. But this kiss was different. This was a kiss with a purpose that was neither tender nor carnal. I don’t know quite how to explain it other than to tell you that I had the impression it was scientific—clinical. It was more like a download; a kiss that was psychic, that transmitted information; a kiss from another dimension that has lingered with me for decades. It was as if Umberto was attempting to awaken something in me—something I could feel but didn’t understand, and I remember thinking in the middle of it: “this is the strangest kiss I have ever experienced.”

We stopped at a cafe in the village for coffee. The drive back to Paris in the rain was quiet. I kept thinking about his kiss.

We stopped at a cafe in the village for coffee. The drive back to Paris in the rain was quiet. I kept thinking about his kiss.

During the next few weeks Debbie would tell me that she was leaving Paris and I would move from the rue de Lubeck to Pitou’s apartment on the avenue Foch. Umberto didn’t call and, as my old phone number went dead, I figured I’d never see him again. But then, one morning that Spring when I was alone at Pitou’s, the phone rang.

“How did you get this number?” I asked.

“I have my ways,” Umberto said. “Can you have dinner with me? Tonight?”

I was intrigued. Where had he been? Why, suddenly, was he calling? Still, I hesitated.

“It’s important,” he said. “Please have dinner with me.”

He took me to Les Pieds dans l’Eau, a little restaurant that sits on the Seine in Neuilly. All these years later, I still remember what he ordered—barely anything, a salad, some soup. He didn’t eat meat. I was so accustomed to having him grill me about my life, wanting to know every possible detail, that I told myself I wouldn’t let him out of my sight without learning more about him.

He took me to Les Pieds dans l’Eau, a little restaurant that sits on the Seine in Neuilly. All these years later, I still remember what he ordered—barely anything, a salad, some soup. He didn’t eat meat. I was so accustomed to having him grill me about my life, wanting to know every possible detail, that I told myself I wouldn’t let him out of my sight without learning more about him.

“Tell me about your family, in Rome,” I asked.

“They’re not really my family,” he answered. “I’m not from Rome.”

“Oh,” I remarked while sipping my wine. “Then, where are you from?”

Without hesitating, and with a deadly serious expression across his face, he answered.

“I’m not from here.”

“What do you mean?”

“I’m not from Earth,” he continued. “I’m from another planet.”

I started to laugh.

Umberto had never demonstrated a sense of humor. And yet, he had caught me by surprise in the best way. I was happy I didn’t have food in my mouth at that moment. I think I would have spit it out.

“Yeah, right,” I giggled. “No, really, tell me where you’re from.”

His expression suddenly changed, to bemusement, as if he held a secret that he couldn’t let me in on; as if he was thinking: “She doesn’t remember.”

“I’m from another planet,” he repeated, articulating each word slowly.

This time when he said it, I didn’t laugh. In a split second, it had become clear to me that he wasn’t joking.

“Ask me,” he continued. “You have all sorts of questions running through your head right now. Ask me.”

“What planet?”

“It’s in the Pleiades,” he answered.

“How did you get here?”

“A vessel.”

“Where is it?”

“In Switzerland.”

“How long have you been here?”

“Several years . . . we’re trapped, we can’t get back right now.”

“But, you look just like we do. I thought . . .”

“. . . that I’d be green?” he asked, while finishing my sentence with an enigmatic smile. “What else do you want to know?”

For a moment, just contemplating my questions had me feeling stupid. I thought back to my years at Westlake and the yarns that Arrelle would spin for me, privately, only to finish by laughing in my face while proclaiming: “You’re so naïve, Berenice.” Then, again, how naïve is it to believe that of all the trillions of constellations out there, ours is the only one with “intelligent” life?

Swiftly, I became the inquisitor and Umberto calmly and happily complied, answering all of my questions with specific detail.

“Our planet is much like yours,” he continued. “But it’s bigger.”

“Is the vegetation the same?”

“Yes, but the dominant color on our planet is different. It’s blue.”

“But that’s the dominant color here,” I remarked. “The sky is blue, the ocean is blue. . .”

“. . . but the vegetation is green.”

“You mean, the leaves on your trees are blue?”

“Yes, for the most part. The bushes and the grass too. Our atmosphere doesn’t have the same composition as Earth’s. The photosynthesis occurring there adapts to the light differently.”

I wouldn’t have any reason to believe that a blue planet could exist for another 36 years. Then, one day, in the Spring of 2008, I fell across an article in Scientific American written by Nancy Kiang, a biometeorologist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. The color of plants, she explained, on any given planet depends upon the spectrum of its star’s light and the filtering of that light by air and water. Astronomers classify stars based on color—color that relates to temperature, size and longevity of the star. We classify these stars in order from hottest to coolest as F, G, K and M stars. Our sun is a G star. F stars are larger, burn brighter . . . and bluer. For F star planets, the flood of energetic blue photons is so intense that it is thought that plants might need to reflect them using a screening pigment similar to anthocyanin, giving their leaves a blue tint. And because blue photons carry more energy than red or green ones, plants growing under the light from an F star might need to harvest only the blue light to grow, discarding the lower quality green photons through red light.

I wouldn’t have any reason to believe that a blue planet could exist for another 36 years. Then, one day, in the Spring of 2008, I fell across an article in Scientific American written by Nancy Kiang, a biometeorologist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. The color of plants, she explained, on any given planet depends upon the spectrum of its star’s light and the filtering of that light by air and water. Astronomers classify stars based on color—color that relates to temperature, size and longevity of the star. We classify these stars in order from hottest to coolest as F, G, K and M stars. Our sun is a G star. F stars are larger, burn brighter . . . and bluer. For F star planets, the flood of energetic blue photons is so intense that it is thought that plants might need to reflect them using a screening pigment similar to anthocyanin, giving their leaves a blue tint. And because blue photons carry more energy than red or green ones, plants growing under the light from an F star might need to harvest only the blue light to grow, discarding the lower quality green photons through red light.

If so, F star foliage would, indeed, look blue.

If so, F star foliage would, indeed, look blue.

Umberto’s eyes glimmered with excitement, his lips holding on to a state of delight at the thought that, slowly, I was casting off my skepticism.

“What else do you want to know?” he asked.

“What do you do for a living?” I said, finally asking the one question that preoccupies all earthlings.

“What do you mean?” he responded, quixotically.

“For money,” I answered. “What do you do to make money?”

Uproariously, he began to laugh.

“Money!” he said. “We don’t use money. We don’t need it!”

“Money!” he said. “We don’t use money. We don’t need it!”

He continued laughing at my question after giving me his answer.

“But . . . that’s not possible,” I protested. “How do you pay for things?”

“Why would you think we have to pay for anything?”

“We’ll, how are any of the resources on your planet allotted?”

“Fairly,” he answered. “But you can’t understand our way of life if you are not willing to abandon the paradigm you’ve been taught to accept. So much is hidden from you. Have you ever thought that you’ve been conditioned?”

It was a polite way of asking me if I had ever thought that I’ve been brainwashed.

Umberto spoke of many things that evening; of a civilization where people don’t “work” but, rather, dedicate their lives to their passions, to what each one of them does best; of crystalline living structures, gigantic towers—straight out of Dubai’s near future—which do not need fossil fuels to light or to heat. He spoke of caring beings who co-operate in a spirit of co-creation in a world where police forces don’t exist. Yet none of these concepts of extra-terrestrial existence was more difficult for me to wrap my head around than the thought that, where Umberto comes from, money does not exist.

Umberto spoke of many things that evening; of a civilization where people don’t “work” but, rather, dedicate their lives to their passions, to what each one of them does best; of crystalline living structures, gigantic towers—straight out of Dubai’s near future—which do not need fossil fuels to light or to heat. He spoke of caring beings who co-operate in a spirit of co-creation in a world where police forces don’t exist. Yet none of these concepts of extra-terrestrial existence was more difficult for me to wrap my head around than the thought that, where Umberto comes from, money does not exist.

“It’s a tool of control,” he continued. “We are not controlled, Bérénice. We are free.”

“Free?” I asked. “But money is what makes you free. It defines freedom.”

He smiled.

“Surely you are more imaginative than that.”

Then, lifting his head, he shot through me with Thoreau.

“In your world,” he continued, “there are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil, to one who is striking at the root.”

I was silent as jumbled thoughts cascaded in a down flow of confusion.

“Then, why are you here?” I wondered out loud.

“There are a lot of us here,” he answered. “We’ve been visiting you for thousands of years.”

I thought back to the sci-fi imagery that, inexplicably, appears throughout ancient art; of spacemen in suits on Italian cave drawings that date back to 10,000 B.C., of the prehistoric French cave paintings depicting disk shaped ships; and, more recently, of the Egyptian renditions of space vehicles from the Temple of Seti at Luxor.

I thought back to the sci-fi imagery that, inexplicably, appears throughout ancient art; of spacemen in suits on Italian cave drawings that date back to 10,000 B.C., of the prehistoric French cave paintings depicting disk shaped ships; and, more recently, of the Egyptian renditions of space vehicles from the Temple of Seti at Luxor.

“So, this isn’t your first trip?” I asked

“In your time? Over two hundred years ago.”

“I see. Did you ever meet Louis XIV?”

“I know you believe me,” he laughed. “Why are you joking?”

“How do you know I believe you?”

“Because you are wondering how old I am. It’s your next question.”

“The same way I knew that you wanted tea on the afternoon when I first saw you.”

I was silent as I pondered the possibility that this man had read my thoughts from the second he had spotted me walking past the water basin at the epicenter of the Champ de Mars.

“To answer your question, we live much longer than you do.”

“How much longer?”

“Seven hundred, eight hundred years. Approximately.”

“Ah,” I answered. “Then, just how old are you?”

“About 360 earth years,” he smiled.

“So . . . if we were to meet forty years from now . . . you’d look exactly the same?”

He smiled while nodding his head affirmatively.

I ordered desert. He didn’t. He seemed content just to watch me eat . . . and question, and think .

“Why are you telling me all of this,” I asked, as he signaled the waiter for the bill.

It was the one question he didn’t answer.

“Let’s take a walk,” he said. “It’s such a beautiful night.”

We weren’t far from the Eiffel Tower and he chose to take me back to the spot where we had first met—the park that stretched for 60 acres behind it.

“Do you mind if I stop at my place to pick up a jacket?” he asked. “It’s a bit chilly.”

Not far from the park, he drove into a modern complex of highrise apartment buildings. Leaving his car at the front entrance, I thought I’d wait for him. But he beckoned to me.

“Come. Come up with me.”

For a moment, I thought that his need for a jacket had been a ploy, the excuse to lure me up to his apartment. What twenty-year-old girl wouldn’t think such a thought? But if the suspicion re-entered my mind while riding the elevator up to his floor, it was immediately dispelled once he opened his door.

We were high up, at least twenty floors, and the city lights shown brightly through oversized plate-glass windows. The carpet was white, but the rooms were empty. The phone from the bedroom was ringing as we entered. I followed Umberto as he rushed to answer it. There was a mattress, covered in white sheets, on the floor. A lamp, that was lit, sat next to it by the phone on the carpet. His closet was open. Two shirts, a pair of slacks and a leather jacket hung from a wooden bar. That was it. Nothing else, in the entire apartment. Clearly, this man was a visitor with no intention of staying.

“No, don’t worry.” I heard him say. “I’ll be there.”

Hanging up, he grabbed his jacket.

“Shall we go?” he asked.

We walked the entire length of the Champ de Mars that night, past the hôtel particulière that one day in the near future would be my home. The park is replete with Masonic symbols. In fact, its design is drawn according to the Freemason sacred geometry of Da Vinci’s L’Uomo Vitruviano. Leonardo’s famous drawing depicts a man in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart, inscribed in a circle and square. It is based upon geometric correlations of ideal human proportions described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise De architectura. Vitruvius contended that the human figure is the principal source of proportion among the classical orders of architecture; proportion that the eye immediately recognizes as beautiful, a Fibonacci ratio that we refer to as “golden,” found over and over in nature—from the leaf arrangement in plants, the spiral pattern of the florets of a flower, or the bracts of a pine cone, to the relation between the parts of our bodies—both human and celestial.

We walked the entire length of the Champ de Mars that night, past the hôtel particulière that one day in the near future would be my home. The park is replete with Masonic symbols. In fact, its design is drawn according to the Freemason sacred geometry of Da Vinci’s L’Uomo Vitruviano. Leonardo’s famous drawing depicts a man in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart, inscribed in a circle and square. It is based upon geometric correlations of ideal human proportions described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise De architectura. Vitruvius contended that the human figure is the principal source of proportion among the classical orders of architecture; proportion that the eye immediately recognizes as beautiful, a Fibonacci ratio that we refer to as “golden,” found over and over in nature—from the leaf arrangement in plants, the spiral pattern of the florets of a flower, or the bracts of a pine cone, to the relation between the parts of our bodies—both human and celestial.

I had met Umberto in the park’s belly, the solar plexus chakra of the Vitruvian Man. With Da Vinci’s drawing superimposed over a satellite image of the grounds, the Eiffel Tower is conspicuously situated at his root chakra, the Muladhara. It is not the only curious correlation to the “energetic wheels” of the Renaissance man.

I had met Umberto in the park’s belly, the solar plexus chakra of the Vitruvian Man. With Da Vinci’s drawing superimposed over a satellite image of the grounds, the Eiffel Tower is conspicuously situated at his root chakra, the Muladhara. It is not the only curious correlation to the “energetic wheels” of the Renaissance man.  The Human Rights Monument, commissioned by Francois Mitterrand during his presidency, is located at his heart chakra. Emblazoned across the west wall of the temple monument that faces the central part of the gardens, a Masonic angle bracket and delta are featured in high relief, with two obelisks at either side of the inscription above the triangle. Most intriguing, however, is L’Uomo Vitruviano’s third eye chakra—the spot that corresponds to his pineal gland. It is marked by

The Human Rights Monument, commissioned by Francois Mitterrand during his presidency, is located at his heart chakra. Emblazoned across the west wall of the temple monument that faces the central part of the gardens, a Masonic angle bracket and delta are featured in high relief, with two obelisks at either side of the inscription above the triangle. Most intriguing, however, is L’Uomo Vitruviano’s third eye chakra—the spot that corresponds to his pineal gland. It is marked by  the obelisk at the Place de Fontenoy, directly behind l’École Militaire.

the obelisk at the Place de Fontenoy, directly behind l’École Militaire.

Descartes referred to the pineal gland as “the seat of the soul,” a star-gate to other dimensions, to the invisible counterpart of the visible universe where our Higher-Self resides. This tiny pine cone shaped organ, at the center of the brain, remains a mystery to modern-day scientists. Yet, throughout the ages, it has been thought sacred. Symbolized as the single horn of the unicorn, the lone feather of the Indian medicine man, the tip of the Egyptian Staff of Osiris and, perhaps, most famously, as

Descartes referred to the pineal gland as “the seat of the soul,” a star-gate to other dimensions, to the invisible counterpart of the visible universe where our Higher-Self resides. This tiny pine cone shaped organ, at the center of the brain, remains a mystery to modern-day scientists. Yet, throughout the ages, it has been thought sacred. Symbolized as the single horn of the unicorn, the lone feather of the Indian medicine man, the tip of the Egyptian Staff of Osiris and, perhaps, most famously, as  the eye of Horus, it is the spiritual cognition center in the brain. Even Catholicism pays homage to it. According to popular medieval legend, in ancient Rome, an enormous bronze sculpture, the “Pigna,” in the shape of a huge pine cone three stories tall, stood on top of the Pantheon as a lid for the round opening in the center of the building’s vault. And, in Ancient Rome, the Pigna served as a large fountain, overflowing with water, next to the Temple of Isis. Today, a gigantic statue of it sits directly in front of the Vatican, in the “Court of the Pine Cone.”

the eye of Horus, it is the spiritual cognition center in the brain. Even Catholicism pays homage to it. According to popular medieval legend, in ancient Rome, an enormous bronze sculpture, the “Pigna,” in the shape of a huge pine cone three stories tall, stood on top of the Pantheon as a lid for the round opening in the center of the building’s vault. And, in Ancient Rome, the Pigna served as a large fountain, overflowing with water, next to the Temple of Isis. Today, a gigantic statue of it sits directly in front of the Vatican, in the “Court of the Pine Cone.”  Mysteriously, Catholic religious tradition is intricately interwoven with pine cones, perhaps most prominently atop the sacred staff carried by the Pope himself. Even the Coat of Arms of the Holy See, found on the Vatican flag among other places, features a stacking of three crowns suspiciously similar in shape to a pine cone. Indeed, the very name, “Holy See,” appears to be a direct reference to the organ in our bodies that we refer to as our Third Eye.

Mysteriously, Catholic religious tradition is intricately interwoven with pine cones, perhaps most prominently atop the sacred staff carried by the Pope himself. Even the Coat of Arms of the Holy See, found on the Vatican flag among other places, features a stacking of three crowns suspiciously similar in shape to a pine cone. Indeed, the very name, “Holy See,” appears to be a direct reference to the organ in our bodies that we refer to as our Third Eye.

And, made of the same cellular material as the optic nerve, why wouldn’t this enigmatic gland provide us with sight? With Insight. For if it is the logical left side of the brain that talks, and the creative right side of the brain that laughs, it is the pineal gland, sitting between the two, that bridges the gap, allowing them to communicate with each other.

And, made of the same cellular material as the optic nerve, why wouldn’t this enigmatic gland provide us with sight? With Insight. For if it is the logical left side of the brain that talks, and the creative right side of the brain that laughs, it is the pineal gland, sitting between the two, that bridges the gap, allowing them to communicate with each other.

The “All-Seeing Eye” of the Masonic Brethren, the “Eye Single” of the Scriptures by which the body is filled with light, the “One Eye” of Odin which enabled him to know all the Mysteries, are all allusions to this primitive organ that, unwittingly, we have allowed to be petrified until it no longer functions. At least, for most of us. Exposed to a high volume of blood flow, the tissues of the pineal gland are easily calcified, save for those alert to the devastating effect of the fluoride in our toothpaste and tap water.

The fluoride deception, perpetrated upon us in the early Fifties, was orchestrated by none other than Edward Bernays. During World War II the Nazi’s tested fluoride in concentration camps and found it to numb the minds of their captives. Fluoride literally calcifies the pineal gland, rendering it useless. Yet, selling the toxin was child’s play for Bernays. He understood the unconscious and illogical trust the American public places in medical authority, and used it to help Alcoa, and other special interest groups, convince us that water fluoridation is safe. By hiding behind the screen of the American Dental Association, and stressing a claimed public-health benefit for our teeth, the master propagandist effortlessly engineered our consent to be poisoned.

The fluoride deception, perpetrated upon us in the early Fifties, was orchestrated by none other than Edward Bernays. During World War II the Nazi’s tested fluoride in concentration camps and found it to numb the minds of their captives. Fluoride literally calcifies the pineal gland, rendering it useless. Yet, selling the toxin was child’s play for Bernays. He understood the unconscious and illogical trust the American public places in medical authority, and used it to help Alcoa, and other special interest groups, convince us that water fluoridation is safe. By hiding behind the screen of the American Dental Association, and stressing a claimed public-health benefit for our teeth, the master propagandist effortlessly engineered our consent to be poisoned.

“You can get practically any idea accepted,” Bernays said chuckling in a 1993 interview to journalist Christopher Bryson. “If doctors are in favor, the public is willing to accept it, because a doctor is an authority to most people, regardless of how much he knows, or doesn’t know.”

“You can get practically any idea accepted,” Bernays said chuckling in a 1993 interview to journalist Christopher Bryson. “If doctors are in favor, the public is willing to accept it, because a doctor is an authority to most people, regardless of how much he knows, or doesn’t know.”

Over the past century, the bombardment of toxic material on this one organ has been so consequential that, as a result, most of us have been condemned to a perpetual state of apathy and low motivation only overcome in rare moments of extreme joy or severe grief. Which may be why bereft widows often recount the lucid dream experience of being with their loved ones shortly after their deaths. Dreams so vivid that they can feel the touch of their departed and smell their skin. Dreams so real that it may be they are not dreaming at all but, rather, out of extreme pain, have found the way to reunite with their beloved by passing through a door into a parallel dimension; a portal available to all of us . . . through the pineal gland.

Serving as our sixth sense, could it be that our pineal gland can free us from the prison created by the other five?

For the answer to this question, you need only observe your children and grandchildren while they are still very small. They have an extremely sensitive area around the crown of the head where, prior to the seventh year, the skull has not yet fully formed. The sensitivity of this area over the Third Eye during childhood is often accompanied by a phase of clairvoyance. These are the years when children play with “imaginary” friends, where, through the open gateway of the pineal gland, they are still living largely in the invisible world with which they were once fully connected.

“So much is hidden from you.”

I thought back on Umberto’s words as I gazed from my living room window toward Gustave Eiffel’s tower.

It was beautifully lit on that evening when we had last walked together, through the park gardens. A number of people had been out, enjoying the night air.

It was beautifully lit on that evening when we had last walked together, through the park gardens. A number of people had been out, enjoying the night air.

“Do you know what your name means?” Umberto asked. “Bérénice . . . do you know what it means?”

Up until then, I had never thought of a person’s name as meaning anything.

“It’s Greek,” he said. “But it was probably most commonly used among the Ptolemy ruling family of Egypt. It means bringing victory.”

“And Umberto?” I asked. “ What does Umberto mean?”

“Warrior,” he answered. “It means renowned warrior.”

“Is this your way of telling me that we’d make a good team?” I joked.

I made him laugh again—for the first time, by trying to.

“Strange that I should have met you in the field of Mars,” I continued, “the grounds named after the Romans’ Campus Martius as a tribute to their god of war. What battle are you waging, Umberto?”

But, for the second time that night, he didn’t answer me.

“You may not see me for a while,” he said, changing the subject. “But, don’t worry.”

As he uttered his words, the penetrating warmth of his smile fell upon me like the downpour from a hot shower. I didn’t want to move.

I like to think that Umberto gave me my mystical sense, or maybe it was just that he awakened it with his kiss. After meeting him, my curiosity for the metaphysical world burgeoned. I began delving into literature devoted to the studies of extrasensory perception, clairvoyance, reincarnation and parallel universes. I found myself drawn to books on the Knights Templar, Freemasonry and the secrets of the occult. Suddenly, their symbology was everywhere; on the facades of important buildings, on the back of the dollar bill, and in the ancient art of Egypt and Mesopotamia I had spent so much of my youth studying and where I should have noticed it long ago. I contemplated their hierarchy of degrees that leads to illumination–of initiate status as a first degree “Entered Apprentice” all the way up to the 33° position of “Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret.” And I wondered what that Secret might be. Could I attain it simply by allowing my “Spirit Fire” to travel up the thirty-three degrees of my spinal cord where, bursting upon the hypothalamus, it would open my Third Eye?

I like to think that Umberto gave me my mystical sense, or maybe it was just that he awakened it with his kiss. After meeting him, my curiosity for the metaphysical world burgeoned. I began delving into literature devoted to the studies of extrasensory perception, clairvoyance, reincarnation and parallel universes. I found myself drawn to books on the Knights Templar, Freemasonry and the secrets of the occult. Suddenly, their symbology was everywhere; on the facades of important buildings, on the back of the dollar bill, and in the ancient art of Egypt and Mesopotamia I had spent so much of my youth studying and where I should have noticed it long ago. I contemplated their hierarchy of degrees that leads to illumination–of initiate status as a first degree “Entered Apprentice” all the way up to the 33° position of “Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret.” And I wondered what that Secret might be. Could I attain it simply by allowing my “Spirit Fire” to travel up the thirty-three degrees of my spinal cord where, bursting upon the hypothalamus, it would open my Third Eye?

“Bérénice?”

I turned from the window to see Pitou standing in our entrance hall in front of the dining room, the pillars of our Masonic Temple framing his sides. He had some papers in hand and was peering over the rims of his reading glasses to look at me.

“Qu’est-ce qu’il y a, mon chou? Tu as l’air triste.”[1]

“I was just reminiscing,” I answered, while thinking of what William Faulkner had once said of memories: “The past is never dead, it is not even past.”

And so it is with Umberto. For, that evening, in late November of 1971, was the last time I saw him; yet, he is still with me. And I still hold out hope that, once again, he will appear in my life as mysteriously as he did on that afternoon in the park. After all, in Pleiadian time, forty-five years is only “a while”—a little while.

[1] “What’s wrong, darling? You look sad.”

Next Post: Paris- The Cinderella Years: “L’Amour, L’Amour”

Click on the Dust Jacket, below, to be taken to the Post.

At the end of each post, I will guide you to the next one.

Thank you so much. I love reading your memories from the seventies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So happy to hear it Nathalie.

LikeLike

Wonderful…timeless…the pyramids of La Defense…my photo on the construction wall…mirror reflecting my joy at gazing into the setting sun. Living in the modern tower at Place de Trocadero..of a friend living in Champs de Mars …drawn to the bowels of the nearby library…the thirst of discovery…the quarters on Ave Foch. Ahh Paris…the old souls …discovering better my long soul journey… my life-changing astral voyage…into the universe. But first…at the lei line point of L’Eglise Saint Sulpice ..I escaped with firca fortnigjt with Thor. Thank you Berenice…for this enlightening companion sight Csrol Ann.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the lovely comment, Carol

LikeLike

Thank you for this extraordinary chapter. It manages to elevate previous chapters as well, guiding readers through timeless Paris–megaliths to cathedrals–reminding us that the ancient, eternal city has been spiritual vortex forever. Your scholarly mentions of the elements of higher conscious woven into Umberto’s story, the role of the pineal gland (our third eye that permits us to ‘see the light’) & your openness to asking & accepting big questions & their answers creates an anticipation for coming chapters & participation in this incandescent young woman’s growth of wisdom in the City of Light. The gods, the spirits, the nine sacred danseuses have clearly made her one their own!

LikeLiked by 2 people

LOVE this comment

LikeLike

Can only smile! Because of my spirituality, no words necessary…communicating thoughts without it…Third Eye takes it in. Wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is remarkable. You were truly blessed to have met Pitou. I look forward to the rest of your memoirs.

LikeLike